<dependency>

<group>junit</group>

<name>junit</version>

<version>4.13</version>

<scope>test</scope>

</dependency>Dependabot and automated dependency upgrades

11 octobre 2020

Tags: gradle dependabot

Dependabot starts with a great idea: the state of our industry, in terms of dependency management, is sad. In particular, maintaining dependencies up-to-date is difficult and while some solutions exist, the vast majority of projects are out of date. This isn’t a big deal for bugfixes and feature updates, but it is clearly a problem for security issues.

Therefore, any kind of automation to make the situation better is a good idea. I am in deep empathy with people working in this area: this is a difficult problem and there are no perfect solutions: as an example, in order to improve security of builds and reduce the risks of attacks via the toolchain, Gradle introduced dependency verification as a first-class citizen. We deeply care about security and definitely support any attempt to make things better in this area.

The genius idea about Dependabot is that it does it at scale and submits pull requests that you just have to review and merge if everything goes ok.

The best example in the Java ecosystem happened yesterday: the JUnit team fixed a security vulnerability in JUnit 4.13. At first, you might wonder what kind of security problems you can have with a testing framework, which, by definition, just like a build tool, runs any arbitrary code on your machine. The reality is that most people are unaffected by this problem: it would only be the case if your tests write sensitive data (like credentials) in a shared environment, or that you somehow expose whatever is written in the test directory to the outside world.

Nevertheless, because it’s a CVE, Dependabot submitted automated pull-requests to all projects using JUnit 4 and Dependarmaggedon happened: tens of thousands of pull requests. This might sound cool, a security fix needs to be fixed, but I find this noisy, and in the end dangerous.

Here’s why.

Automatic detection

Dependabot is as good as an automated tool can be. I mean that its implementation, at least in the Java and JVM ecosystem in general, is too simplistic and that it’s inherently wrong. I don’t have the expertise to tell if it’s different in the other supported ecosystems (Go) but I suspect a lot of the problems I’m going to describe here exist also in those ecosystems.

In practice, Dependabot is nothing more than a search and replace engine: it looks into some particular files that it knows about (think pom.xml), looks for some patterns, then tries to identify dependency coordinates and eventually replaces them. I’m simplifying a bit, because it does some interpretation of the versions it finds, for example to match version ranges, but that’s roughtly how it works.

For example, it will identify this:

and it will replace the 4.13 with 4.13.1, then submit a PR for you to review. WIN!

Yes, and no. Because this is extremely easy to defeat.

First, as I said, it only looks for known files. For Maven, it’s pretty simple, there’s only one place to look for: pom.xml files, but for other build tools, like Gradle, Ivy, Ant, Bazel, Pants, … that’s not the case: dependencies can be declared in different files, not all named the same. Dependency versions can be separate (in properties files) or inherited from context (parent POMs, platforms, …).

A more complete strategy is to look for patterns too, like .gradle, but then, they also miss the .gradle.kts files (they do), or the plugins which can contribute dependencies.

In short: it’s a whack-a-mole game.

One must think that it’s not a big deal, because catching some cases is better than not catching at all, and I agree, but that’s not the expectation when you read what the tool promises.

In the end, any tool which tries to parse build files and tries to interpret its model based on string evaluations is doomed to fail.

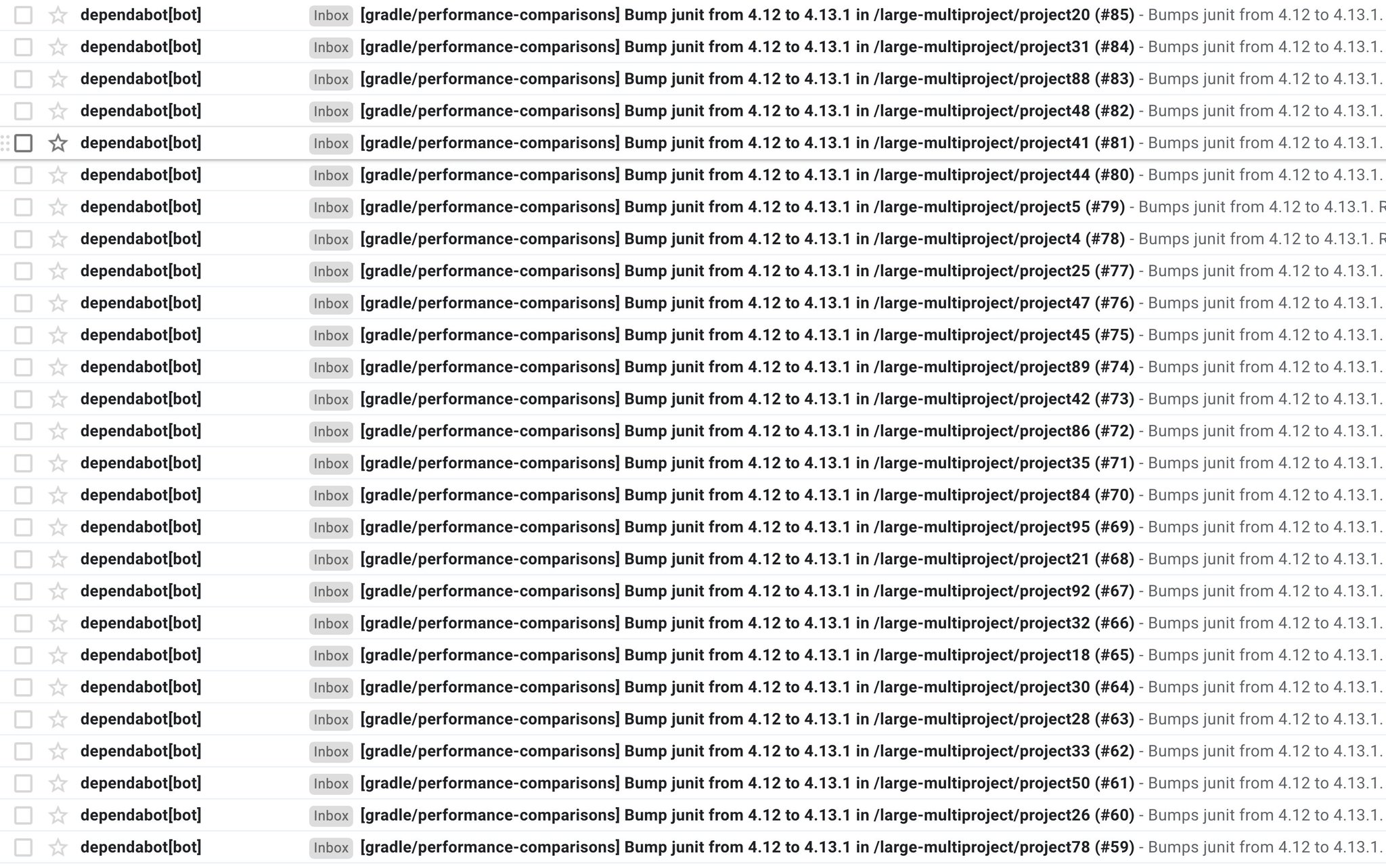

Even if it manages to catch some problems, things can go wrong. As an example, here’s what we got at Gradle for this JUnit upgrade:

For a single repository, it created dozens of individual pull requests to ask us to upgrade. That’s nice of you, Dependabot, but it’s totally missing the point: this repository contains generated code, used in performance testing. The way the code is layout, the repetition of dependency declarations, etc, everything is intentional.

If you put apart the fact that Dependabot could have created a single pull request for all dependencies, instead of creating hundreds, it highlights a general problem with those automated detection tools:

Context matters!

At Gradle, we often receive emails from security teams telling us things like: "The Gradle distribution contains a dependency on this X library which has vulnerability Y". However, in almost all cases we’ve investigated, this was a no issue for us. Because of the nature of Gradle, the fact that by definition it runs arbitrary code on a machine, most vulnerabilities are not a problem in this environment: context matters. What’s more, even if your tool uses a library that has a critical vulnerability (we use Jackson for example, which had a number of thems recently), it doesn’t mean that your code exercises the path which is vulnerable: context matters!

It’s not harmful to upgrade, but it creates a lot of noise.

Wrong impression of security

But the biggest problem with such tools, and again I’m using Dependabot as an example, is that they give a wrong impression of security.

As I explained, Dependabot will basically read your POM files, or Gradle files, or whatever build tool files you use, and assume that the version it reads is the version which is going to be used. We, as developers, and even more as build tool authors, know that this is wrong: the dependencies you declare are rarely the ones you resolve.

That’s the reason why tools like NPM (Javascript), Gradle (multi-language) or Cargo (Rust) make use of dependency locking. Dependency locking is a concept which helps with build reproducibility. Say, for example, that you write:

dependencies {

implementation 'org.mylib:awesome:[1.0, 2['

}This means that Gradle can pick whatever version of awesome as long as it’s in the range.

This is a typical declaration for semantic versioning, when you expect a library to be upgradable up to the next major.

In Gradle you can even improve this by explaining what version you prefer in the range, if nobody else cares:

dependencies {

implementation('org.mylib:awesome') {

version {

require '[1.0, 2['

prefer '1.3'

}

}However, ranges come at a price: if a new dependency version is released, your build would suddenly start using this new version, which breaks reproducibility in case you checkout old code, for example, for a bugfix. Therefore, as soon as you use ranges (and by extension any dynamic dependency version), you should use it with dependency locking. Dependency locking will make sure that whatever version of a library resolved at time T is used at time T+N even if a new version is out. It does so by writing the result of the dependency resolution process in a lock file.

Upgrading dependencies becomes an intentional process that you do from time to time by generating a new lock file.

What is the relationship with tools like Dependabot?

By using the versions you declare, they have absolutely no guarantee that the versions you resolve are not vulnerable.

In the example above, imagine that I use range [1.0, 2[ and that I’m resolving 1.3.

At some point in time, version 2.1 is released and is vulnerable.

You could imagine that because you used a range and that 2.1 is out of the range, you are safe.

That’s what those tools would assume, but they would be wrong: the reality is that despite this declaration, by the play of conflict resolution (Ivy, Gradle, …) or ordering (Maven), a totally different version can be selected, even 2.1!

Again there are tools to mitigate this problem, but the reality is that by just reading the declaration, you’re not safe.

It’s even worse than that: what about transitive dependencies?

Imagine that you have:

Foo → Bar → Baz

And that you depend on Foo. What if a vulnerability is discovered on Baz? Will you be notified? What kind of automated pull request can such a tool make to make sure that you upgrade Baz?

Can we do better?

I have some good and bad news for you.

The good news is that we can do better. The bad news is that it’s not easy.

First, instead of relying on the declaration, those tools should really rely on the result of dependency resolution. If, for example, they used the lock files instead of the build files, they would know exactly what a build resolves. This, however, is only possible if the build uses dependency locking, and only for dependency graphs which are actually locked. It’s a reasonable assumption to say that what is locked is the most relevant information, though.

Of course, I said there were bad news. As soon as you use the resolution result, you almost have to give up on automated remediation (pull requests). One thing they could do is patching the lock file. However, this is in general not a good idea, because, as I explained, lock files are generated: they present to you the result of resolution. Partially upgrading a lock file, manually, is possible but then you cannot make any guarantee that the app is going to work, because introducing a different dependency version may introduce different transitive dependencies!

An alternate solution is to gather the information about resolved dependencies during the build: this is what build scans do for Gradle and Maven, for example. This information can be extracted during the build and Dependabot would know precisely, reliably, what is resolved by a project. We even offer a Tooling API to do this kind of work.

Then there’s remediation. This is the hardest problem. Because what most people like about Dependabot is actually the automated remediation: pull requests are nice, we all love that.

But say, that to fix the transitive dependency issue above, Dependabot suggested to add a first level dependency with a different version.

For Maven, this would work, since it’s order and depth sensitive.

But it would break your model: the application doesn’t depend on Baz: it depends on Foo, which, by the transitive game, depends on Baz.

You don’t want to introduce a first level dependency on Baz because it doesn’t make sense.

For Gradle, you could use dependency constraints instead: constraints are meant for this use case. A constraint adds, as it name implies, a constraint to the equation of the resolution of the graph (a bit like in constraint programming). They would participate in the dependency graph resolution if, and only if, the dependency they talk about appears in the graph. In that sense, they don’t break the application model, by introducing arbitrary first-level dependencies.

Our Java ecosystem is polluted by hundreds of accidental first level dependencies and exclusions because of this lack of modeling: it is important to get things right.

Last but not least, how you declare dependencies matters. In Gradle, using rich version constraints, you can explicitly reject bad versions, and you can explain why.

Conclusion

In conclusion, I think that Dependabot’s intent is legitimate and that today it’s better than nothing. Let’s detect projects using vulnerable dependencies and propose automated remediation.

We, as build tool authors, also need to consider the wider context, which is dependency resolution in general, which isn’t as simple as it seems. In particular we consider that detection is an easy problem if you use the right tools, while remediation is a hard one.

I think the current implementation of Dependabot is mostly wrong (at least in the Java ecosystem) as it relies on the declaration. This raises a number of issues: - it is dependent to the patterns it recognizes - it assumes that what you see is what you get - it cannot recognize transitive dependencies actually resolved by your project, so it misses real vulnerabilities - it doesn’t matter about the context of use of your dependencies

The context thing is difficult to solve, but it’s actually painful because of the noise it creates, in case the "vulnerable dependency" is actually not in your case. However, I think there are improvements which can me made by actually using the actual resolution results instead. Then it raises some interesting technical challenges, like how to sandbox execution of builds (GitHub actions already do this) but more importantly how to create an automated pull request from the result of the analysis.

Note that I also understand that from a Dependabot creator point of view, having to implement build-tool specific logic, like calling the Tooling API, to gather information about resolved dependencies might sound scary. I still think this is the right thing to do to be correct and, if our goal is really to make the industry safer, that’s what we should do. However, we have alternate solutions. For example a few weeks ago I experimented with a fork of my friend and colleague Paul Merlin’s Gradle Command GitHub Action which automatically generates a JSON file of resolved dependencies during the build.

Schalk Cronjé also mentioned to me the OWASP plugin, which I forgot to mention when I originally wrote this blog post, but I think it a great answer and currently better answer because it does exactly what I describe: rely on what you actually resolve, not what you declare, and lets you carefully review the results via a generated report.

I’m not sure this is the best answer, but it shows that we can attack the problem from different angles.

Eventually, the key takeaway of this blog post should be: don’t assume that you are safe because you use Dependabot. You’re not.