Introducing astro4j

22 April 2023

Tags: astronomy astro4j solex java graalvm jsolex

Why astro4j?

I’m a software developer, and if you are following me, you may also know that I’m an amateur astrophotographer. For a long time, I’ve been fascinated by the quality of software we have in astronomy, to process images. If you are french speaking, you can watch a presentation I gave about this topic. Naturally, I have been curious about how all these things work, but it’s actually extremely rare to find open source software, and when you do, it’s rarely written in Java. For example, both Firecapture (software to capture video streams) and Astro Pixel Processor are written in Java, but both of them are closed source, commercial software.

Last month, for my birthday, I got a Sol’Ex, an instrument which combines spectrography and software to realize amazing solar pictures in different spectral lines. To process those images, the easiest solution is to use the amazing INTI software, written in Python, but for which sources are not published, as far as I know, neither on GitHub or GitLab.

|

Note

|

After announcing this project, I have been notified that the sources of INTI are indeed available, as GPL. It’s a pity they are not linked on the webpage, this would have helped a lot. |

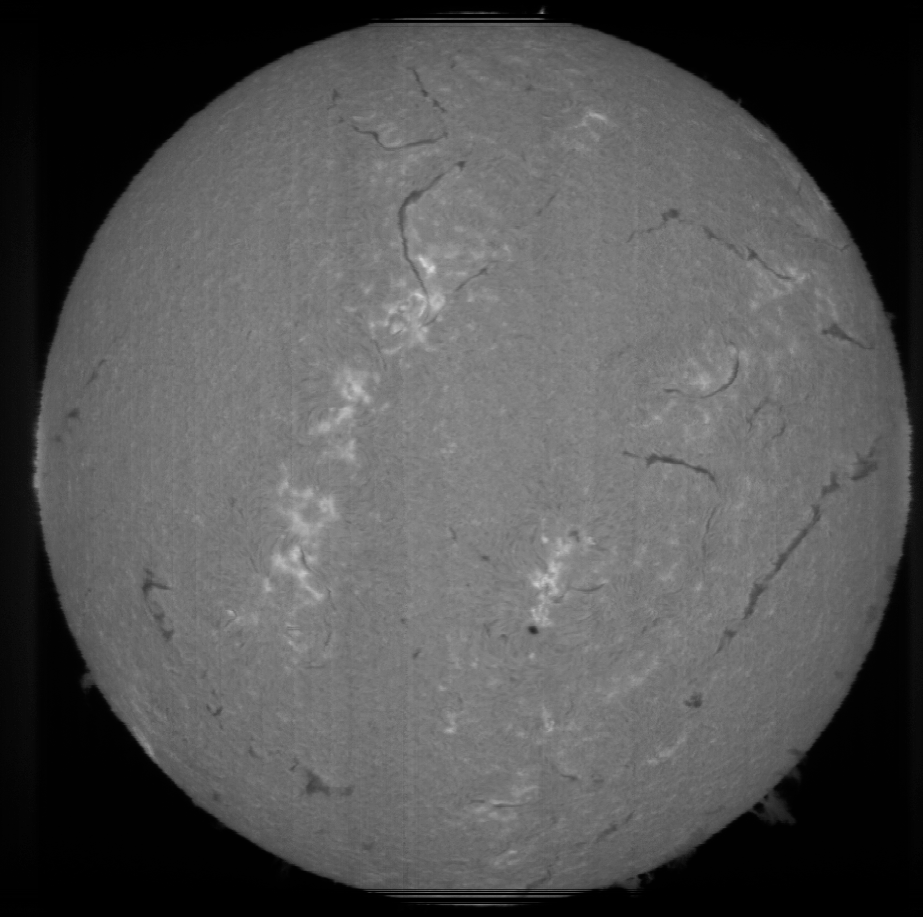

To give you an example of what you can do, here’s the first photography I’ve done with Sol’Ex and processed with INTI (color was added in Gimp):

To get this result, one has to combine images which look like this:

Interesting, no? At the same time, I was a bit frustrated by INTI. While it clearly does the job and is extremely easy to use, there are a few things which I didn’t like:

-

the first, which I mentioned, is that it’s using Python and that the sources are not published (as far as I understand, some algorithms are not published yet). I am not surprised that Python is used, because it’s a language which is extremely popular in academics, with lots of libraries for image processing, science oriented libs, etc. However, because it’s popular in academics also means that programs are often written by and for academics. When we’re talking about maths, it’s often short variable names, cryptic function names, etc…

-

second, after processing, INTI pops up a lot of images as individual windows. If you want to process a new file, you have to close all of them. The problem is that I still haven’t figured out in which order you have to do this so that you can restart from the initial window which lets you select a video file! Apparently, depending on the order, it will, or will not, show the selector. And sometimes, it takes several seconds before it does so.

-

INTI seems to be regenerating a font cache every time I reboot. This operation takes several minutes. It’s probably an artifact of packaging the application for Windows, but still, not very user friendly.

-

INTI generates a number of images, but puts them alongside the videos. I like things organized (well, at least virtually, because if you looked at my desk right now, it is likely you’d feel faint), so I wish it was creating one directory per processed video.

Confronting the old demons

When I started studying at University, back in 1998, I was planning to do astrophysics. However, I quickly forgot about this idea when I saw the amount of maths one has to master to do modern physics. Clearly, I was reaching my limits, and it was extremely complicated for me. Fortunately, I had been doing software development for years already, because I started very young, on my father’s computer. So I decided to switch to computer science, where I was reasonably successful.

However, not being able to do what I wanted to do has always been a frustration. It is still, today, to the point that a lot of what I’m reading is about this topic, but still, I lack the maths.

It was time for me to confront my old demons, and answer a few questions:

-

am I still capable of understanding maths, in order to implement algorithms which I use everyday when I do astronomy image processing with software written by others?

-

can I read academic papers, for example to implement a FFT (Fast Fourier Transform) algorithm, although I clearly remember that I failed to understand the principles when I was at school?

-

can I do this while writing something which could be useful to others, and publish it as open source software?

Astro4j is there to answer those questions. I don’t have the answers yet and time will tell if I’m successful.

Using modern Java

One question you may have is why Java? If you are not familiar with this language, you may have this old misconception that Java is slow. It’s not. Especially, if you compare to Python, it’s definitely not.

This project is also for me a way to prove that you can implement "serious science" in Java. You can already find some science libraries in Java, but they tend to me impractical to use, because not following the industry standards (e.g published on Maven Central) or platform-dependent.

I also wanted to leverage this to learn something new. So this project:

-

uses Java 17 (at least for libraries, so that they can be consumed by a larger number of developers, for applications I’m considering moving to Java 20)

-

uses JavaFX (OpenJFX) for the application UI

-

experiments with the Vector API for faster processing

As I said, my initial goal is to obtain a software which can basically do what INTI does. It is not a goal to make it faster, but if I can do it, I will.

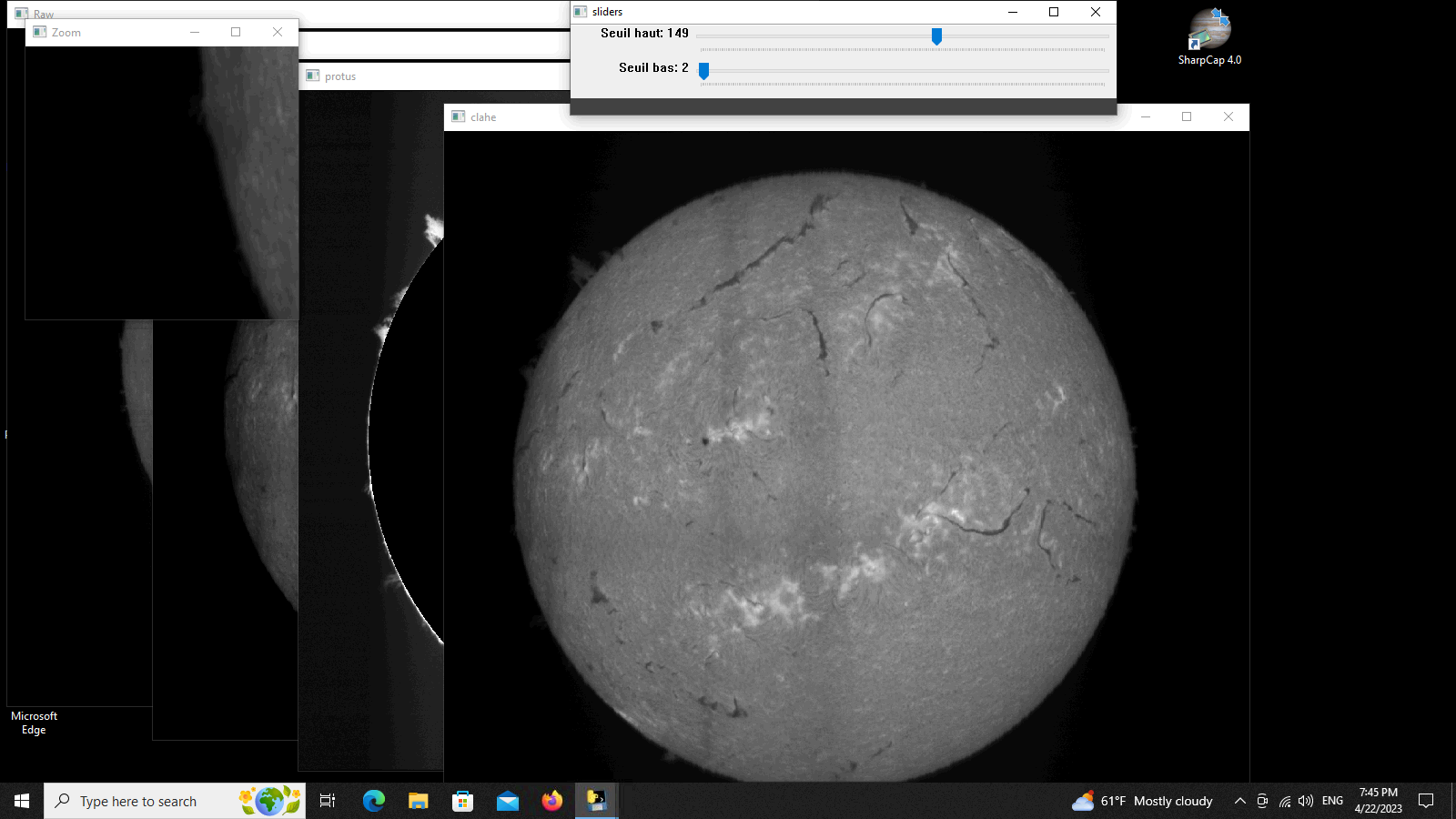

Introducing JSol’Ex

After a few evenings (and a couple week-ends ;)), I already have something which performs basic processing, that is to say that it can process a SER video file and generate a reconstructed solar disk. It does not perform geometry correction, nor tilt correction, like INTI does. It doesn’t generate shifted images either (for example the doppler images), but it works.

Since the only source of information I had to do this was Christian Buil’s website and Valérie Desnoux INTI’s website, I basically had to implement my own algorithms from A to Z, and just "guess" how it works.

In order to do this, I had to:

-

implement a SER video file decoder. The library is ready and performs both decoding the SER file and performs demosaicing of images

-

on top of the decoder, I implemented a SER file player, which is still very basic at this stage, and uses JavaFX. This player can even be compiled to a native binary using GraalVM!

Here’s an example:

Then I could finally start working on the Sol’Ex video processor. As I said, I don’t know how INTI works, so this is all trial and error, in the end…

In the beginning, as I said, you have a SER video file which contains a lot of frames (for example, in my case, it’s a file from 500MB to 1GB) that we have to process in order to generate a solar disk. Each frame consists of a view of the light spectrum, centered on a particular spectral line.

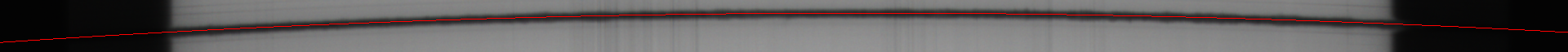

For example, in the following image, we have the H-alpha spectral line:

Because of optics, you can see that the line is not horizontal: each frame is distorted. Therefore, in order to reconstruct an image, we have to deal with that distortion first. For this, we have to:

-

detect the spectral line in the frame, which I’m doing by implementing a simple contrast detection

-

perform a linear regression in order to compute a 2d order polynomial which models the distortion

Note that before doing this, I had no idea how to do a 2d order regression, but I searched and found that it was possible to do so using the least squares method, so I did so. The result is that we can identify precisely the line with this technique:

In the beginning, I tought I would have to perform distortion correction in order to reconstruct the image, because I was (wrongly) assuming that, because each frame represents one line in the reconstructed image, I had to compute the average of the colums of each frame to determine the color of a single pixel in the output. I was wrong (we’ll come to that later), but I did implement a distortion correction algorithm:

When I computed the average, the resulting image was far from the quality and constrast of what I got with INTI. What a failure! So I thought that maybe I had to compute the average of the spectral line itself. I tried this, and indeed, the resulting image was much better, but still not the quality of INTI. The last thing I did, therefore, was to pick the middle of the spectral line itself, and then, magically, I got the same level of quality as with INTI (for the raw images, as I said I didn’t implement any geometry or tilt correction yet).

The reason I was assuming that I had to compute an average, is that it wasn’t clear to me that the absorption ray would actually contain enough data to reconstruct an image. As it was an absorption ray, I assumed that the value would be 0, and therefore that nothing would come out of using the ray itself. In fact, my physics were wrong, and you must use that.

A direct consequence is that there is actually no need to perform a distortion correction. Instead, you can just use the 2d order polynomial that we’ve computed, and "follow the line", that’s it!

Now, we can generate an image, but it will be very dark. The reason is obvious: by taking the middle of the spectral line, we’re basically using dark pixels, so the dynamics of the image are extremely low. So, in order to have something which "looks nice", you actually have to perform brightness correction.

The first algorithm I have used is simply a linear correction: we’re computing the max and min value of the image, then rescaling that so that the max value is the maximum representable (255).

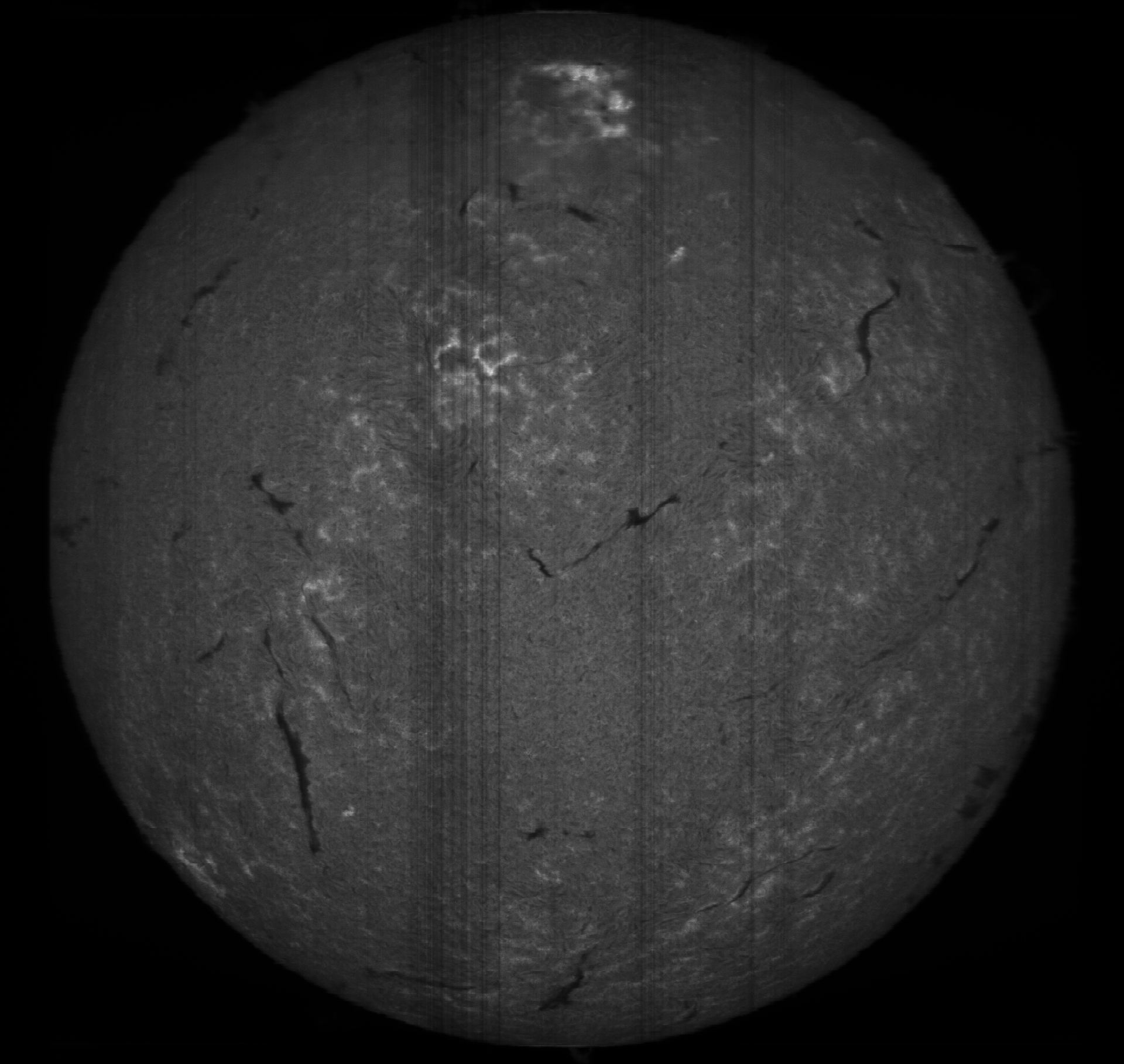

Here’s the result:

However, I felt that this technique wouldn’t give the best results, in particular because linear images tend to give results which are not what the eye would see: our eye performs a bit like an "exponential" accumulator, the more photos you get, the "brighter" we’ll see it.

So I implemented another algorithm which I had seen in PixInsight, which is called inverse hyperbolic (Arcsinh) correction:

Last, you can see that the image has lots of vertical line artifacts. This is due to the presence of dust either on the optics or the sensors. INTI performs correction of those lines, and I wanted to do something similar.

Again, I don’t know what INTI is doing, so I figured out my own technique, which is using "multipass" correction. In a nutshell, for each row, I am computing the average value of the row. Then, for a particular row, I compute the average of the averages of the surrounding lines (for example, 16 rows before and after). If the average of this line is below the average of the averages(!), then I’m considering that the line is darker than it should be, computing a correction factor and applying it.

The result is a corrected image:

We’re still not a the level of quality that INTI produces, but getting close!

So what’s next? I already have added some issues for things I want to fix, and in particular, I’m looking at improving the banding reduction and performing geometry correction. For both, I think I will need to use fast fourier transforms, in order to identify the noise in one case (banding) and detect edges in the other (geometry correction).

Therefore, I started to implement FFT transforms, a domain I had absolutely no knowledge of. Luckily, I could ask ChatGPT to explain to me the concepts, which made it faster to implement! For now, I have only implemented the Cooley-Tukey algorithm. The issue is that this algorithm is quite slow, and requires that the input data has a length which is a power of 2. Given the size of the image we generate, it’s quite costly.

I took advantage of this to learn about the Vector API to leverage SIMD instructions of modern CPUs, and it indeed made things significantly faster (about twice as fast), but still not at the level of performance that I expect.

I am trying to understand the split radix but I’m clearly intimidated by the many equations here… In any case I printed some papers which I hope I’ll be able to understand.

Conclusion

In conclusion, in this article, I’ve introduced astro4j, an open source suite of libraries and applications written in Java for astronomy software. While the primary goal for me is to learn and improve my skills and knowledge of the maths behind astronomy software processing, it may be that it produces something useful. In any case, since it’s open source, if you want to contribute, feel free!

And you can do so in different domains, for example, I pretty much s* at UI, so if you are a JavaFX expert, I would appreciate your pull requests!

Finally, here is a video showing JSol’Ex in action: