Blog

Measuring Solar Differential Rotation with JSol’Ex

05 February 2026

Tags: solex jsolex solar astronomy doppler rotation

A Rotating Ball of Plasma

One fascinating aspect of the Sun is that it doesn’t rotate like a solid body. Unlike the Earth, which completes one rotation in 24 hours regardless of latitude, the Sun’s rotation rate varies with latitude: the equator rotates faster than the poles. This phenomenon, called differential rotation, has been studied since the 19th century and remains an important research topic in solar physics.

The equatorial regions of the Sun complete a rotation in approximately 25 days, while near the poles, it takes about 35 days. This differential rotation is thought to play a key role in the solar dynamo mechanism that generates the Sun’s magnetic field and drives the 11-year solar cycle.

In this blog post, I will explain how I implemented a feature in JSol’Ex 4.5.0 that allows amateur astronomers to measure this differential rotation directly from their spectroheliograph data. A common mistake is to think that this measurement is not possible because the spectral dispersion of a SHG like the Sol’Ex is typically around 0.1 to 0.2Å, which larger than the scale of what we’re trying to measure (2 km/s, which is about 0.04Å). In fact, what we are trying to measure requires sub-pixel precision and we can achieve that.

The Doppler Effect

The principle behind the measurement is simple: the Doppler effect. When a light source moves towards us, the wavelength is shifted towards the blue end of the spectrum (blueshift). When it moves away, the wavelength shifts towards the red (redshift).

Since the Sun rotates, one limb is always moving towards us (let’s say the East limb) while the other is moving away (the West limb). By measuring the wavelength shift of a spectral line at both limbs, we can calculate the rotation velocity.

One might wonder about the Earth’s own motion: we orbit the Sun at approximately 30 km/s, which is much larger than the ~2 km/s solar rotation velocity we’re trying to measure. This orbital motion does produce a Doppler shift of the entire solar spectrum. However, this affects equally all points we can measure: this is a global shift which affects all measurements equally and cancels out. The same is true for any radial velocity of the Sun relative to the Earth (which varies slightly throughout the year as Earth’s orbit is elliptical).

The fundamental formula relating Doppler shift to velocity is:

Where:

-

\(\Delta\lambda\) is the wavelength shift

-

\(\lambda_0\) is the rest wavelength of the spectral line (typically the H-alpha wavelength)

-

\(v\) is the velocity along the line of sight

-

\(c\) is the speed of light (299,792 km/s)

The Measurement Methodology

Previous Work

I am not the first person to try to make this measurement in amateur spectroheliography. In 2017, Peter Zetner explained on CloudyNights how to measure differential velocity using a spectroheliograph. He explained this methodology in depth in the Solar Astronomy - Observing, imaging and studying the Sun book. His methodology relies on measurements using the Na D2 line, but can also be applied on other bright lines including the commonly used Fe I line at 5250.2 Å, and involves comparing the pixel intensities, by averaging them at different latitudes. The best results are obtained by performing several scans and averaging data. While this works, I wanted to try a different methodology:

-

Use a single scan: the Doppler images that JSol’Ex or INTI can produce are in general very consistent and show that all the data we need is already present

-

Avoid pixel intensities: these are very sensitive to limb darkening, observing conditions (e.g clouds, even if thin) or vignetting (darkening of the images along the slit)

-

Make it possible to use H-alpha scans, not because they would give an accurate value of the velocity of the photosphere plasma, but because that’s the most widely imaged line in amateur solar observations

The results, of course, will depend on the observed line. The methodology that I describe below is capable of returning reasonable results on several lines (H-alpha, Na D2, Fe I) but will completely fail on some others (e.g Ca II K, typically because the line is too wide).

Let’s dive into the methodology.

|

Note

|

The implementation described here was developed iteratively based on real observations. I’m not a solar physicist, just an engineer trying to extract meaningful data from spectroheliograph captures. The algorithm works reasonably well in practice but should be validated against professional measurements for any scientific application. Therefore why it is advertised as experimental. |

East-West Limb Comparison

The key to understanding the methodology is that it relies on spectral line profile analysis and fitting. It requires extracting the spectral line profiles at different locations of the solar disk, preferably near the limbs where the velocities are highest.

The differential rotation measurement extracts solar rotation velocities by comparing Doppler shifts between East and West limb points at the same heliographic latitude.

For each latitude (say, 20° North), the algorithm:

-

Selects a point on the East limb

-

Selects the corresponding point on the West limb at the same latitude

-

Measures the spectral line position at each point

-

Computes the difference: West - East

This differential approach has a crucial advantage: it cancels out systematic errors. Any instrumental offset, wavelength calibration error, or baseline shift affects both measurements equally and disappears when we take the difference.

However, a single East-West measurement at each latitude is not reliable enough. Seeing conditions, local solar activity, or fitting errors can corrupt individual measurements. To improve accuracy, JSol’Ex samples multiple longitudes across the limb region (typically 14 points from 62° to 88° longitude) and aggregates these measurements. This redundancy allows outliers to be rejected and provides an error estimate based on measurement consistency.

The measured velocity is then:

The factor of 2 appears because we’re measuring the difference between approaching and receding limbs.

From Measured Velocity to Equatorial Velocity

The velocity we measure depends on the geometry: how much of the rotation velocity is projected along our line of sight. At the equator and at the limb, we see the full rotation velocity. At higher latitudes or closer to disk center, we see only a fraction.

The geometric correction factor is:

Where:

-

\(\phi\) is the heliographic latitude

-

\(\theta\) is the heliographic longitude (0° at disk center, ±90° at the limbs)

Finding the Spectral Line Center

The most challenging part of the measurement is accurately determining the center of the absorption line. A shift of just 0.01 Å corresponds to a velocity of about 0.5 km/s, which is significant compared to the typical equatorial velocity of ~2 km/s.

JSol’Ex uses Voigt profile fitting to measure the line center. The Voigt profile is the convolution of a Gaussian and a Lorentzian profile, which accurately models the shape of solar absorption lines. The Gaussian component represents thermal Doppler broadening, while the Lorentzian component represents natural and pressure broadening.

For each measurement point, the algorithm:

-

Extracts a spectral profile from the SER file at the corresponding position

-

Fits a Voigt profile to the absorption line

-

Records the fitted line center position

The configurable "Voigt fit half-width" parameter (default: 2 Å) controls how much of the line wings are included in the fit.

Coordinate Systems

One of the trickier aspects of this implementation is correctly mapping between the different coordinate systems involved. The algorithm starts with heliographic coordinates (where we want to measure) and maps them back to the original SER frames (where the spectral data lives).

1. Heliographic Coordinates (starting point)

We begin by specifying points in heliographic coordinates:

-

Latitude: -90° (south pole) to +90° (north pole)

-

Longitude: 0° at disk center, ±90° at the limbs

This requires two solar parameters computed from the observation date:

-

B0: The heliographic latitude of the disk center (varies throughout the year)

-

P: The position angle of the rotation axis (the "tilt" of the Sun as seen from Earth)

2. Image Coordinates

The heliographic coordinates are converted to pixel positions in the reconstructed image. This involves reversing the corrections applied during reconstruction:

-

P-angle correction

-

Flip/rotation

-

Geometric distortion

-

Tilt angle

-

Cropping

3. SER File Coordinates (destination)

Finally, the image coordinates are mapped to the raw SER video file:

-

Frame number: Position in the scan sequence (derived from x-coordinate)

-

Column: Position along the slit (derived from y-coordinate)

-

Row: Spectral direction (wavelength)

This reverse mapping allows us to extract the exact spectral profile at any heliographic location.

The Data Processing Pipeline

The raw measurements are noisy. To produce a clean rotation curve, JSol’Ex uses a two-stage processing pipeline:

Stage 1: Longitude Aggregation

As described earlier, at each latitude, multiple longitudes are sampled (typically 14 points across the limb region). These measurements are combined using one of three methods (the default is median but you can choose):

-

Median: Robust to outliers, uses the middle value

-

Average: Simple arithmetic mean

-

Weighted Average: Points closer to the limb (where Doppler signal is stronger) get higher weight

The error estimate from this stage represents the consistency of measurements across longitudes.

Stage 2: Latitude Smoothing

Even after longitude aggregation, the latitude-by-latitude measurements remain noisy. Individual latitude bins can still be affected by localized features (sunspots, faculae) or simply measurement scatter.

Since we expect solar rotation to vary smoothly with latitude (following the \(\sin^2\phi\) and \(\sin^4\phi\) terms of the differential rotation law), we can exploit this physical constraint to reduce noise further. JSol’Ex applies a smoothing filter that combines nearby latitude points within a configurable window (default: 5°).

Importantly, the errors from Stage 1 are propagated rather than recomputed from the spread in the smoothing window. This ensures the error bars represent measurement uncertainty, not physical latitude variations.

For the median aggregation:

For the average:

The Outcome and Comparison with Theory

The standard form of the differential rotation law (also known as the Faye formula, even if the original formula didn’t include the 3rd term) is:

Where:

-

\(\phi\) is the heliographic latitude

-

\(A\) is the equatorial rotation rate

-

\(B\) and \(C\) control the decrease in velocity with latitude

JSol’Ex compares measured results with the widely-used coefficients from Snodgrass & Ulrich (1990):

-

\(A = 14.713\) deg/day (equatorial rotation rate)

-

\(B = -2.396\) deg/day

-

\(C = -1.787\) deg/day

This gives an equatorial rotation period of about 24.5 days and a polar period of about 34 days. Converting to linear velocity at the solar surface (radius ≈ 696,000 km), the equatorial rotation velocity is approximately 2.0 km/s.

JSol’Ex also fits its own A, B, C coefficients from your measurements, allowing direct comparison with the reference values.

Results

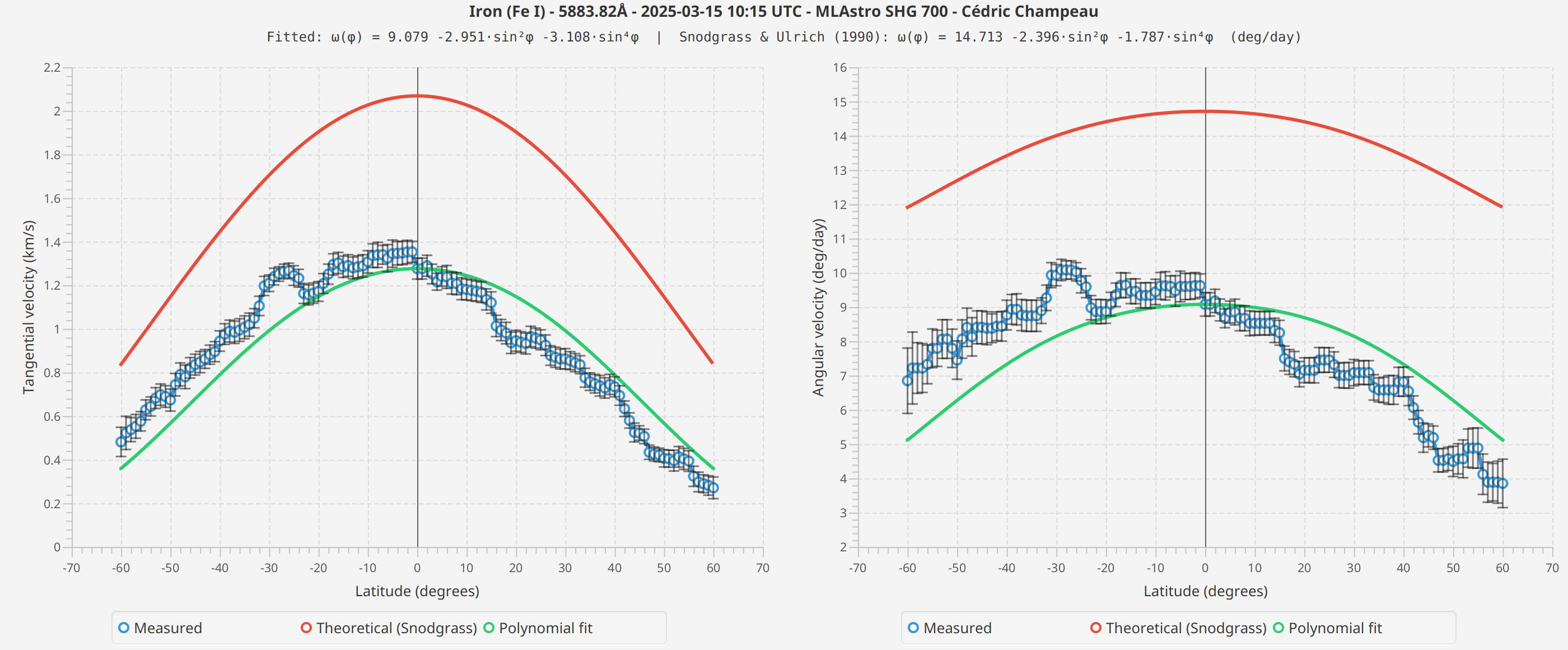

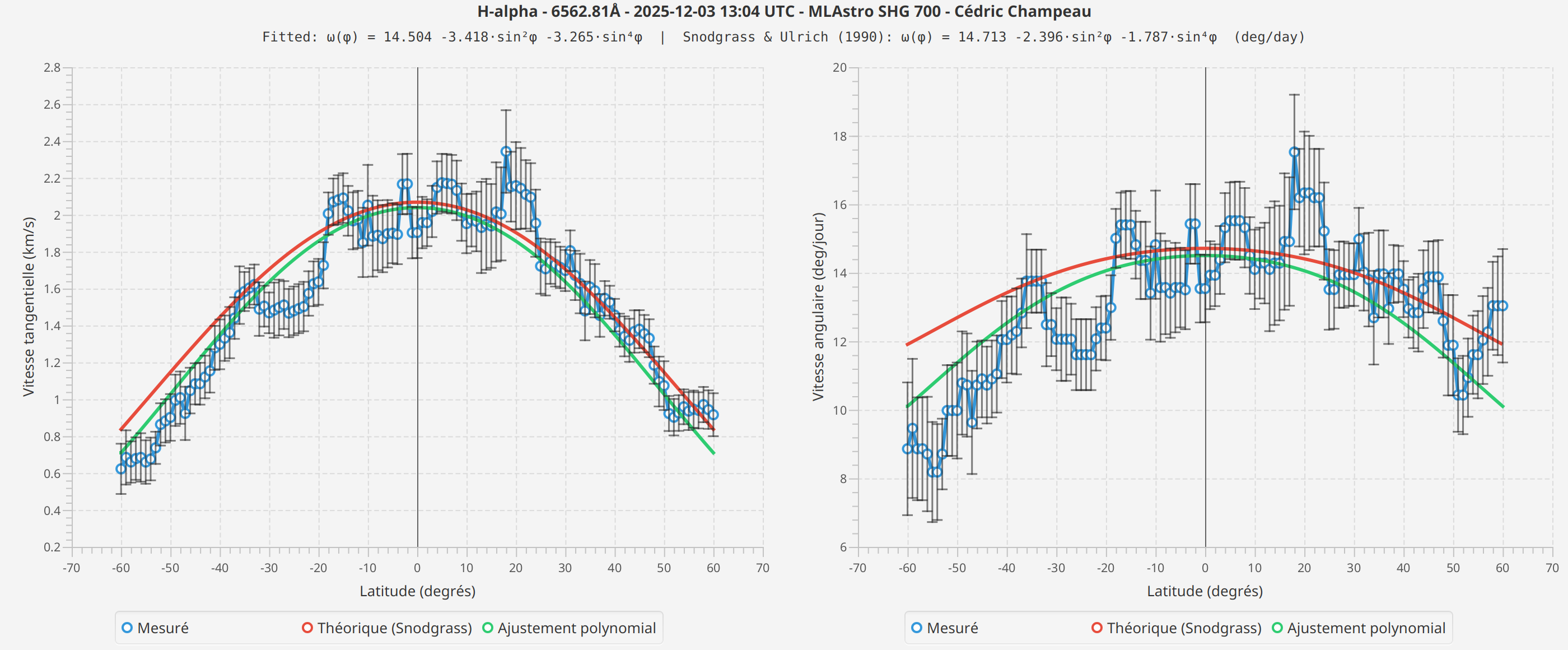

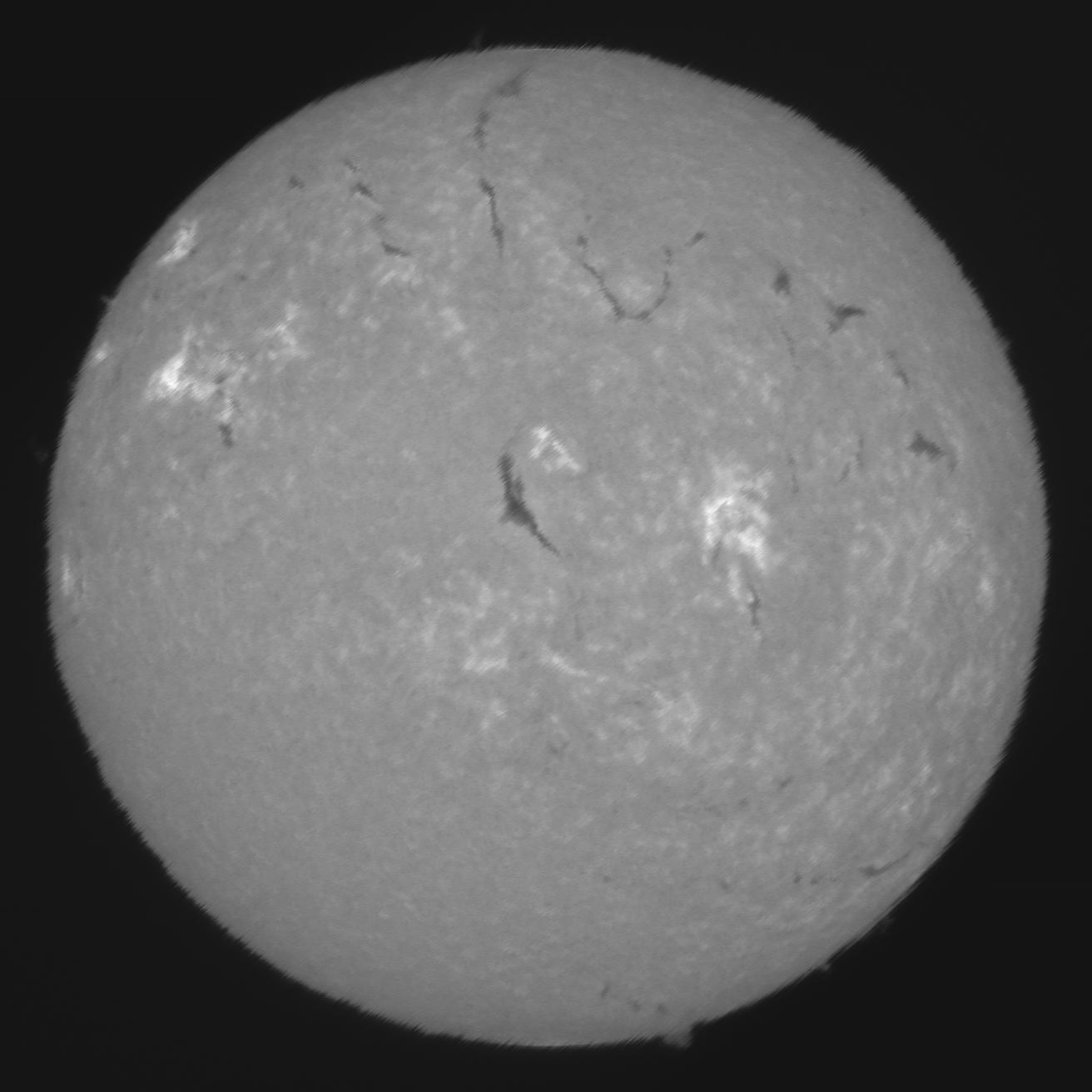

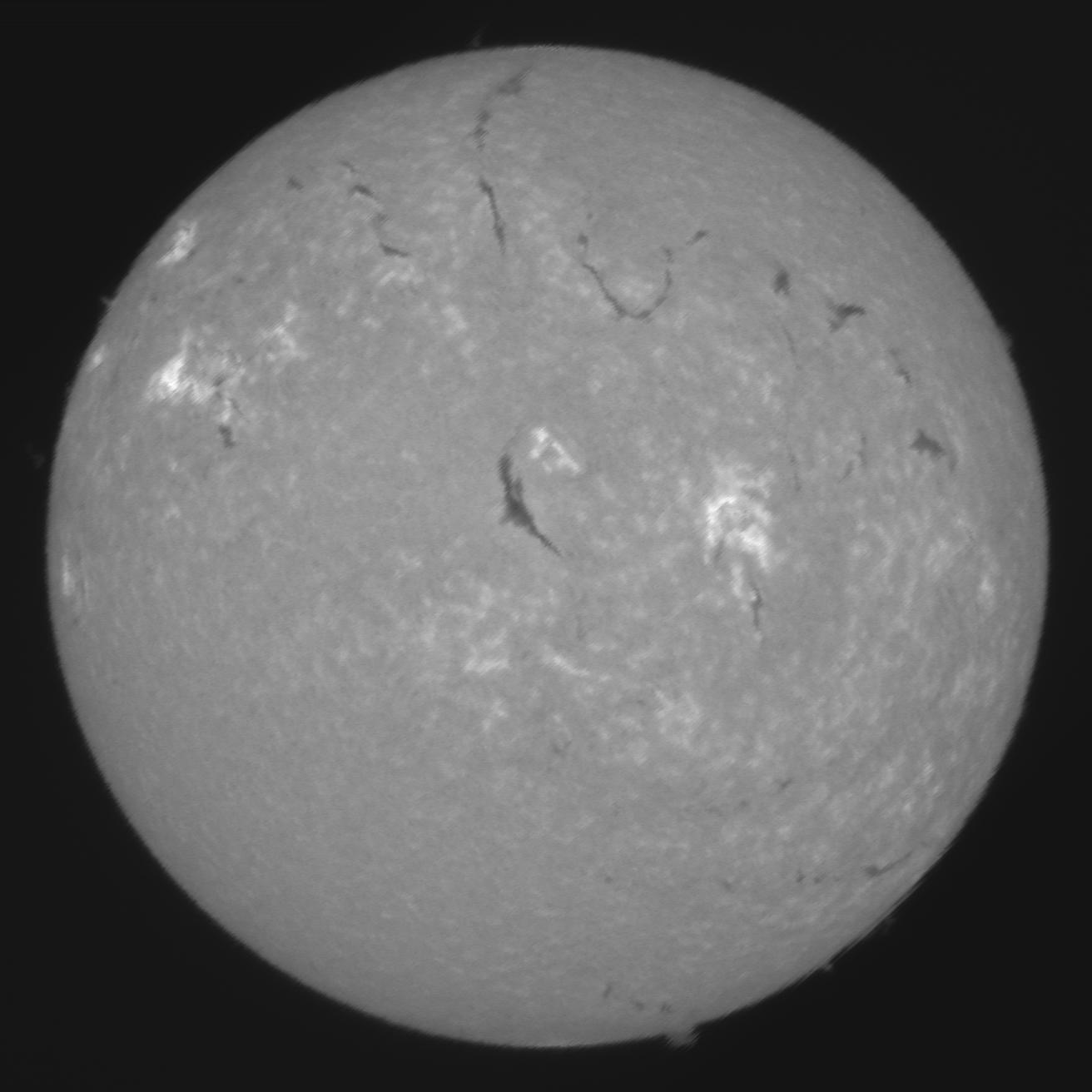

Below are example differential rotation profiles measured with JSol’Ex using two different spectral lines. These measurements were taken on different dates with different seeing conditions.

Fe I 5883 Å

H-alpha

Observations

The measured profiles show the expected general shape: higher velocities at the equator, decreasing toward the poles. The fitted curves follow the theoretical Snodgrass profile reasonably well.

However, I observe differences between spectral lines that I cannot fully explain. The Fe I measurements show different absolute velocities than H-alpha, and the fitted coefficients differ between scans.

Several factors could contribute to these differences:

-

Formation height: Different spectral lines form at different heights in the solar atmosphere, and rotation rates may vary with height (as suggested by recent research from the CHASE mission)

-

Seeing conditions: The scans were taken on different dates with different atmospheric conditions

-

Line profile differences: H-alpha and Fe I have different line widths and depths, which may affect the Voigt fitting precision

-

Systematic effects: There may be instrumental or algorithmic factors I haven’t identified

I present these results as they are, without attempting to draw conclusions about which measurement is "correct" or what causes the observed differences. More measurements across different dates, spectral lines, and instruments would be needed to understand these variations.

Measuring in Practice

The quality of results depends heavily on atmospheric seeing. Poor seeing blurs the spectral lines and makes accurate center determination difficult. Best results are obtained with excellent seeing conditions and a well-focused instrument. Last but not least, a high spectral resolution is preferred, which is normally the case with Sol’Ex (HR) or the SHG 700.

You may also wonder which spectral line you should observe. I tested the algorithm with Fe I, Na D2 and H-alpha, giving the results below. In practice, strong absorption lines should in theory produce the best results, because:

-

The line depth should be sufficient for accurate fitting

-

The wings should be well-defined for Voigt fitting

-

The signal-to-noise ratio should be high

Very broad lines like Ca II K are too wide for accurate Voigt fitting and will produce unreliable results. Too narrow lines may also represent a challenge for Voigt fitting but may work too.

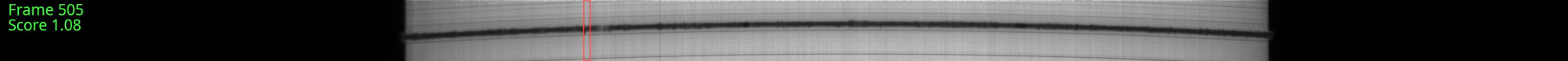

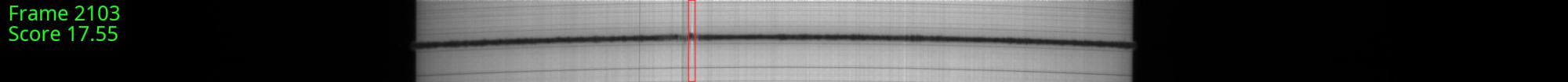

The Impact of the Spectral Line Detection

One subtle but important factor affecting the absolute accuracy of the measurements is the polynomial correction used during image reconstruction. Understanding this is essential for interpreting your results correctly.

During spectroheliograph processing, JSol’Ex computes a polynomial that maps each column position along the slit to the expected row position of the spectral line center. This polynomial is computed from the average of SER frames in the scan (a heuristic is used to include frames containing actual solar data, not sky background).

Such a detection is crucial because the spectral line is not straight across the slit due to optical phenomenons: it consistutes what we often call the "smile". Therefore, the line center might be at row 300 at column 500, but at row 350 at column 1000. The polynomial captures this curvature.

By measuring line positions relative to the polynomial, we effectively remove the optical distortion from our measurements. Without this reference, we would be measuring the sum of optical curvature plus Doppler shift, making it impossible to extract the tiny velocity signals we’re after.

A key question is: why can’t we just measure the absolute position of the spectral line in each frame and compute velocities directly?

The answer lies in the precision required. A velocity of 2 km/s corresponds to a wavelength shift of only ~0.04 Å at H-alpha. With a typical spectral dispersion of 0.1-0.2 Å/pixel, this is a shift of only 0.2 to 0.4 pixels.

The optical curvature across the slit, on the other hand, can easily span 10-30 pixels or more. Any attempt to measure absolute line positions would be completely dominated by this curvature, making Doppler detection impossible.

The polynomial serves as our reference baseline. By measuring how the line position in each individual frame deviates from the polynomial, we isolate the Doppler component from the optical component. This is the key insight that makes sub-pixel precision measurements possible, alongside the Voigt fitting.

A Word About Doppler Images

This, by the way, is also a reason why the Doppler images look different when scanning in RA vs DEC. Because this is a question that is often asked, and that it took months for me to understand the reason, I think it’s worth spending a bit of time explaining the phenomenon. I owe this explanation to Jean-François Pittet and Christian Buil, from a discussion weeks ago on the Sol’Ex mailing list.

RA Scanning vs DEC Scanning: A Critical Difference for Doppler Images

Spectroheliographs can scan the Sun in two directions:

-

RA scanning (Right Ascension): The slit is oriented North-South, and the scan proceeds East-West

-

DEC scanning (Declination): The slit is oriented East-West, and the scan proceeds North-South

This choice has profound implications for Doppler visibility, as explained by Jean-François Pittet on the Sol’Ex mailing list.

RA Scanning: Doppler Visible in Images

In RA scanning mode, each frame captures a vertical slice of the Sun from North pole to South pole. Over the course of the scan:

-

Early frames capture the East limb (approaching, blueshifted)

-

Middle frames capture the disk center (no radial velocity)

-

Late frames capture the West limb (receding, redshifted)

When JSol’Ex computes the polynomial from the average of all frames, the East and West contributions balance out. The blueshift from the East limb is canceled by the redshift from the West limb. The resulting polynomial represents the "neutral" baseline: approximately the line position at disk center with no Doppler shift.

As a result, when we reconstruct the image at pixel shift 0, the Doppler shifts become visible as contrast differences:

-

East limb appears darker (line shifted into the passband)

-

West limb appears brighter (line shifted out of the passband)

This is why Doppler images from RA scans show the characteristic East-West asymmetry.

DEC Scanning: Doppler "Absorbed" by the Polynomial

In DEC scanning mode, each frame captures a horizontal slice of the Sun from East to West. Here’s the critical difference: all pixels within a single frame see approximately the same Doppler shift.

For example, if the current frame is capturing the Eastern half of the disk:

-

All points in that frame are approaching us

-

All points have similar blueshift

When JSol’Ex computes the polynomial from the average of all frames, it doesn’t just capture the optical curvature: it also captures the average Doppler shift across the scan. But here’s the problem: the Doppler shift varies systematically across the scan (East frames are blueshifted, West frames are redshifted).

The polynomial effectively "absorbs" a weighted average of these Doppler shifts. When we then measure line positions relative to this polynomial, much of the Doppler signal has already been subtracted out. The resulting Doppler images will no longer show the rotation of the sun (which can also be a benefit, for other kind of observations).

This is why experienced spectroheliographers often prefer RA scanning for Doppler work: the Doppler signal is more visible and easier to detect.

The P-Angle Complication

There’s an additional subtlety: the Sun’s rotation axis is not perpendicular to the ecliptic. The P-angle (position angle of the rotation axis) varies throughout the year from about -26° to +26°.

Only twice per year (around early June and early December) is the P-angle close to zero. At these times:

-

RA scanning is truly parallel to the solar equator

-

The East-West Doppler pattern aligns perfectly with the scan direction

At other times, when P is non-zero:

-

The rotation axis is tilted relative to the scan direction

-

The Doppler pattern is rotated relative to the image axes

-

Some Doppler signal "leaks" into the polynomial average even in RA mode

This is one reason why differential rotation measurements can show slightly different results at different times of year, despite us taking the P and B0 angles into account.

Implications for Differential Rotation Measurements

This explains why RA scanning is essential for differential velocity measurements:

In RA mode, East and West limb points at the same latitude correspond to the same column on the slit (same slit position, different frames).

The polynomial value at that column is computed from the average of all frames (East limb, disk center, and West limb) so the Doppler shifts cancel out in the average.

When we compute (West - polynomial) - (East - polynomial), the polynomial terms are identical and cancel, leaving us with the true Doppler difference West - East.

In DEC mode, East and West limb points at the same latitude correspond to opposite ends of the slit (different columns, same frame). The polynomial at the East column is computed from frames that all see the East limb at that position, so the polynomial absorbs the blueshift. Similarly, the polynomial at the West column absorbs the redshift. When we compute the difference, these absorbed Doppler shifts don’t cancel: they subtract from our measurement, significantly reducing the measured signal.

This is why, in practice, DEC scans do not produce usable Doppler images or reliable differential velocity measurements.

Configuration Tips

-

Limb longitude (default 75°): Measurements closer to the limb give stronger Doppler signals but risk limb darkening effects

-

Latitude step (default 2°): Smaller values give finer resolution but longer processing times

-

Smoothing window: Should be at least 2× the latitude step for effective smoothing

Conclusion

Measuring differential rotation with amateur equipment would have seemed impossible just a few years ago. Pioneers like Peter Zetner or Christian Buil showed us the path. What I’m trying to do, as always with JSol’Ex, is to make this accessible to even more people at the cost of "magic", which is that some people will very likely share results without understanding the science behind it. I’m not too concerned by this, as I, myself, have been going this way: enjoying SHG image reconstruction, then figuring out how it works, then asking myself questions like "why is it even possible that we measure Doppler velocities so small?": this is an intellectual construct that takes time and we can do better, I think, at brining this to the masses, sharing our insights.

This feature joins the growing list of scientific capabilities in JSol’Ex: Ellerman bomb detection, active region identification, and now differential rotation measurement. Each of these brings professional-level analysis within reach of amateur astronomers, but, as always, be cautious with what I’m saying: I’m not a scientist, just an engineer. I have no doubts that I made approximations, or took liberties that I should probably not have taken.

However, I do think that this brings value to the ecosystem.

Bibliography

Scientific Papers

-

Howard, R. & Harvey, J. (1970) - Spectroscopic determinations of solar rotation. Sol Phys 12, 23-51

-

Snodgrass, H.B. (1984) - Separation of large-scale photospheric Doppler patterns. Sol Phys 94, 13-31

-

Beck, J.G. (2000) - A comparison of differential rotation measurements. Sol Phys 191, 47-70

-

Corbard, T. et al. (2025) - Rotational radial shear in the low solar photosphere. A&A 702, A93

JSol’Ex 4.0.0 est sorti !

11 September 2025

Tags: solex jsolex solaire astronomie ia claude bass2000

Le 18 février 2023, je montais à l’Observatoire du Pic du Midi de Bigorre pour y passer une "Nuit au Sommet", une expérience mêlant observation nocturne et visite des installations scientifiques. J’y ai découvert avec fascination le coronographe Bernard-Lyot, l’expérience CLIMSO gérée par les Observateurs Associés de l’Observatoire Midi-Pyrénées.

Des étoiles plein les yeux (et une en particulier, notre soleil), ma vie d’astronome amateur centrée sur le ciel profond allait basculer vers l’observation de notre Soleil. De retour à la maison, j’ai commencé à me renseigner sur le matériel solaire, et découvrait avec stupéfaction qu’il fallait investir, beaucoup, pour pouvoir observer notre astre en toute sécurité : filtres pleine ouverture, étalons, … tout avait un coût démesuré pour un débutant comme moi. De quoi décourager, jusqu’à ce que je tombe par hasard sur le projet Sol’Ex, initié par la légende Christian Buil.

Ce projet, très didactique, permet de se construire un spectrohéliographe, par impression 3D. Un tel instrument présente de nombreux avantages : coût modeste, résolution élevée et la possibilité d’observer dans de nombreuses longueurs d’ondes tout en mettant à disposition des données exploitables scientifiquement !

L’inconvénient, si c’en est vraiment un, de cet instrument est qu’il ne produit pas une image du soleil observable directement à l’oculaire. Il est nécessaire d’utiliser un logiciel de reconstruction qui, à partir d’une vidéo enregistrant un "scan" du soleil, permet de générer une (voir plus) images du soleil. Ce processus de reconstruction, bien mystérieux pour moi à l’époque, était réalisé par un logiciel écrit par Valérie Desnoux, nommé INTI. Etant développeur (Java), je me suis alors lancé un challenge à l’époque : puisque je ne comprenais pas comment ça fonctionnait, j’allais essayer de créer moi-même un logiciel pour faire cette reconstruction. De cet appétit est né JSol’Ex.

JSol’Ex 4.0 et la collaboration scientifique

Nous voici 2 ans et demi plus tard, JSol’Ex arrive en version 4. Entre temps, le nombre d’utilisateurs a explosé et mon logiciel est exploité non seulement par les utilisateurs du Sol’Ex de Christian Buil, mais aussi pour des spectrohéliographes commerciaux comme le MLAstro SHG 700 (que j’utilise désormais). JSol’Ex a apporté de nombreuses innovations, comme la possibilité d’exécuter des scripts pour générer des animations, faire du stacking, créer des images personnalisées, ou encore la détection automatique d’éruptions, des régions actives (avec annotation), la détection de bombes d’Ellerman, la correction des bords dentelés et j’en passe.

Récemment, JSol’Ex a été utilisé pour réaliser un Atlas de Spectrohéliogrammes, et mentionné dans un article précisément sur la détection des bombes d’Ellerman. Bref, JSol’Ex était devenu suffisamment mature pour faire de la "vraie science", chose qui m’a toujours un peu effrayé pour être honnête.

Ainsi, j’ai toujours refusé d’intégrer une fonctionnalité dans JSol’Ex, qui m’a pourtant été demandée de nombreuses fois : la possibilité de l’utiliser pour soumettre des images dans la base de données BASS2000 de l’Observatoire de Paris-Meudon. Plusieurs raisons à cela : d’une, je ne faisais pas confiance à mon propre logiciel pour sa qualité "scientifique". Si je le savais capable de produire de "belles images", il est tout à fait différent de s’en servir pour une exploitation scientifique. D’autre part, il n’était pas question pour moi d’intégrer une fonctionnalité qui avait été développée par Valérie Desnoux (autrice de INTI) et l’équipe de Meudon sans son accord, par respect pour son travail.

Cependant, vous aurez compris que les temps ont changé et que la pression des utilisateurs ainsi que mes discussions avec Florence Cornu, du projet SOLAP, aux Rencontres du Ciel et de l’Espace fin 2024, puis aux JASON en Juin dernier ont eu raison de mes doutes. Avec son accord et celui de Valérie, je suis donc heureux de vous annoncer que JSol’Ex 4 est officiellement supporté pour soumettre vos images dans la base de données BASS 2000 !

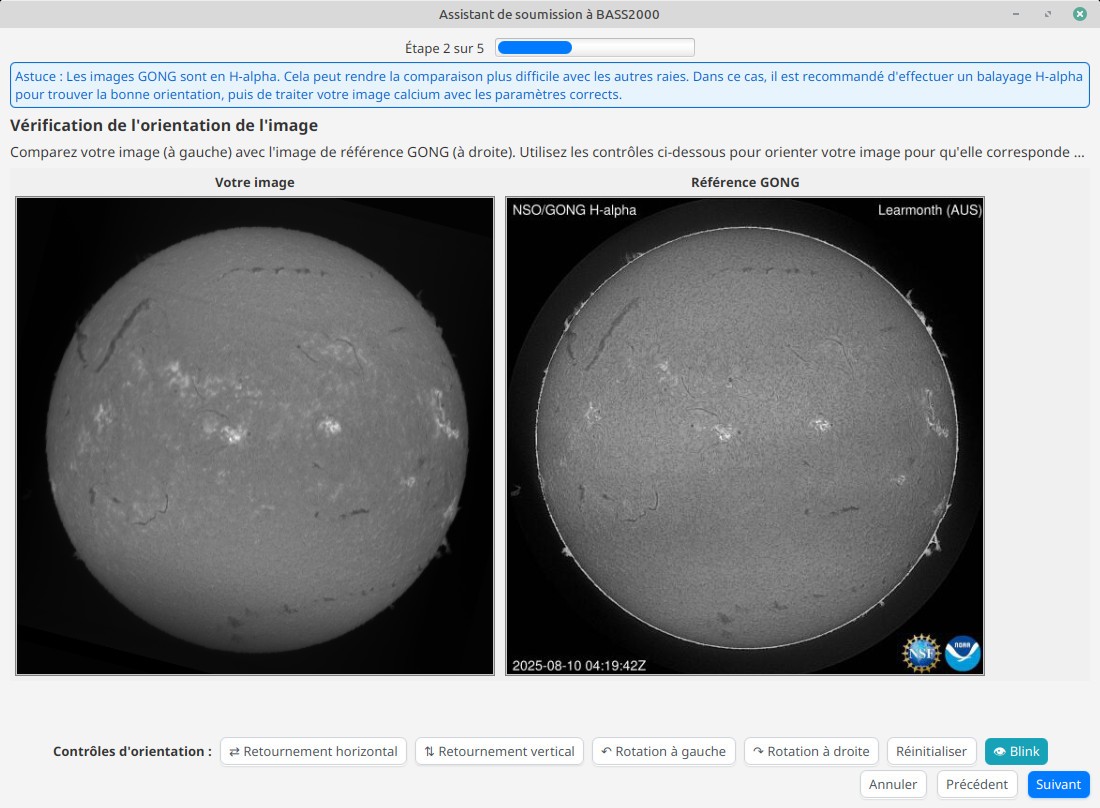

Un assistant pas à pas

Ne souhaitant pas faire les choses à moitié, j’ai particulièrement peaufiné le logiciel pour simplifier cette procédure. J’ai souhaité faire les choses avec sérieux, puisqu’il s’agit d’une base de données professionnelle, exploitée par des scientifiques. Ainsi, une chose importante pour moi était de guider l’utilisateur dans ce processus et de lui faire comprendre l’importance de la qualité des données, tout en simplifiant le processus de soumission.

Ainsi par exemple, BASS2000 n’a que très peu de tolérance sur les problèmes d’orientation de l’image : il faut que le Nord solaire soit à moins de 1 degré d’erreur, sinon l’image sera refusée. L’assistant intègre donc un outil pour aider à vérifier l’orientation et corriger les erreurs minimes dues par exemple à une mise en station imparfaite.

L’assistant guidera aussi l’utilisateur dans son processus de soumission, en lui demandant de bien vérifier toutes les métadonnées associées à l’observation, et ira jusqu’à envoyer l’image sur le serveur FTP de BASS2000 pour validation par les équipes.

Je suis particulièrement reconnaissant à Florence CORNU pour son aide afin que les images JSol’Ex soient acceptées dans la base et je remercie mes beta-testeurs qui ont patiemment testé mes versions de développement pendant l’été.

Je ne vous cache pas qu’il s’agit là d’une forme de reconnaissance de mon travail, des centaines d’heures passées soirs et week-ends à développer ce logiciel qui rappelons-le est entièrement Open Source et gratuit.

Enfin, je ne peux pas m’arrêter sans vous annoncer une deuxième bonne nouvelle : non seulement vous pourrez utiliser JSol’Ex pour soumettre vos images acquises avec un Sol’Ex, mais aussi avec le MLAstro SHG 700, qui devient officiellement supporté dans la base BASS2000 !

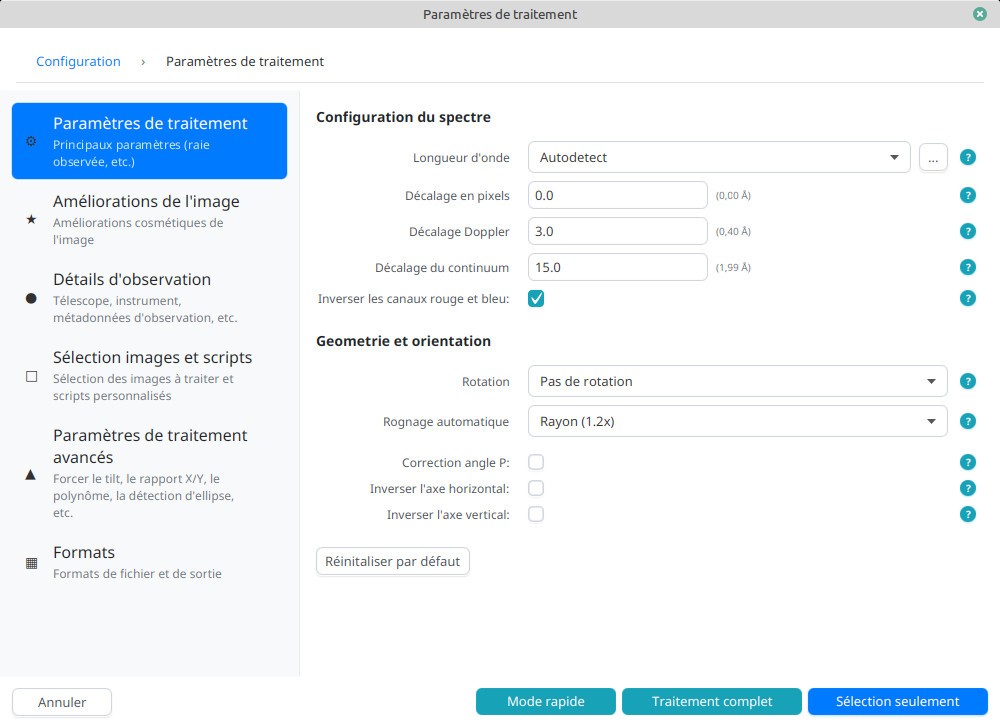

Changements dans l’interface

Pour cette version j’ai aussi souhaité moderniser un peu l’interface graphique et la simplifier : avec le nombre de fonctionnalités croissantes arrive ce moment fatidique que tout développeur redoute : que l’interface ne devienne trop complexe pour les nouveaux utilisateurs et ne parle qu’aux anciens. J’ai essayé d’éviter cet écueil au cours du temps en refusant certaines fonctionnalités trop "de niche", mais sans pouvoir pour autant réussir à avoir une interface totalement claire.

Cette nouvelle version essaie donc de regrouper les paramètres par sections plus claires, tout en ajoutant des infobulles pour guider les utilisateurs, anciens comme nouveaux, dans cet esprit qui est que le logiciel se doit d’être le plus didactique possible : j’essaie, autant que faire se peut, de vous transmettre en tant qu’utilisateurs ce que moi-même j’apprends en développant ce logiciel. Un exemple frappant de cette philosophie, c’est cette fonctionnalité que j’avais ajoutée qui permet de montrer en cliquant sur le disque solaire, à quelle image il correspond dans le fichier source (une vidéo contenant des spectres).

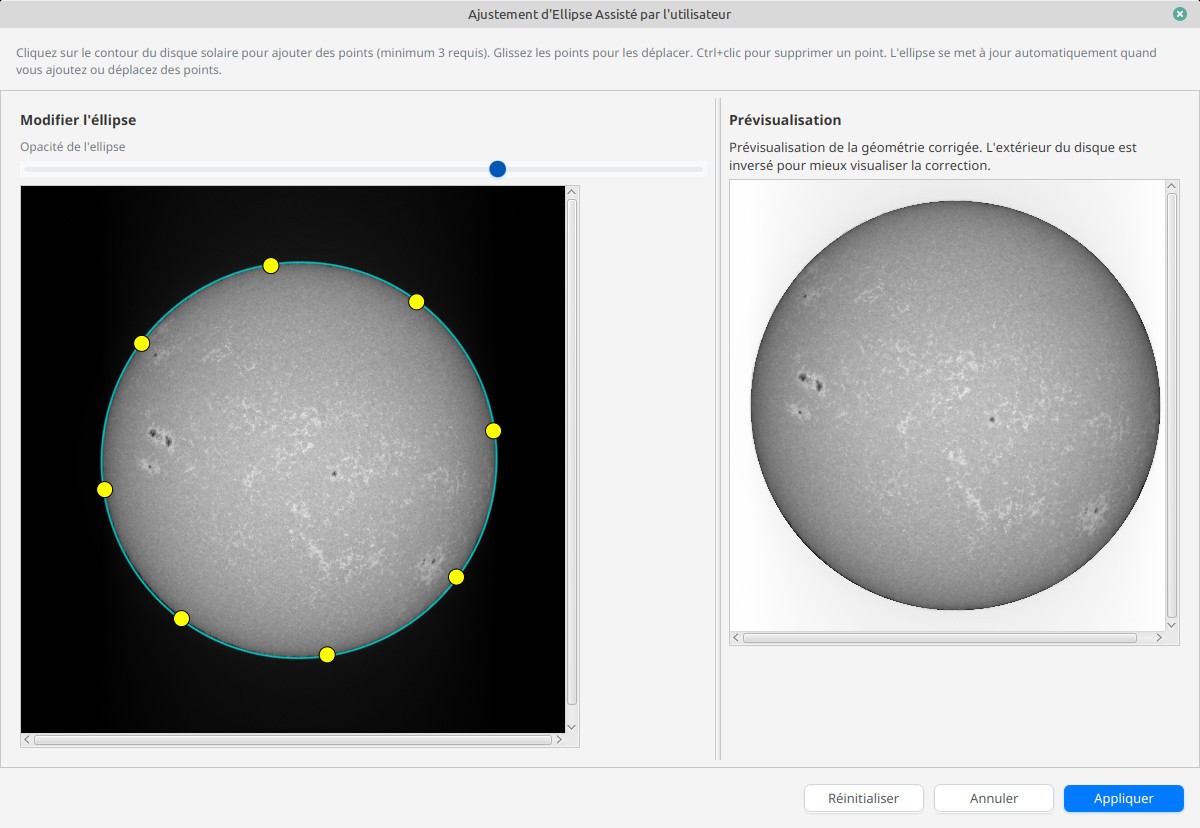

Détection d’ellipse assistée par l’utilisateur

Je vous parlais un peu plus haut de l’Atlas des Spectrohéliogrammes. Cet atlas, réalisé par Pál Váradi Nagy, nécessite un travail énorme d’analyse des données et est réalisé à l’aide de scripts JSol’Ex. Cependant, pour certaines longueurs d’ondes ou pour parfois des images un peu compliquées à traiter, le logiciel peut échouer à détecter correctement les contours du disque solaire. Ceci peut arriver notamment lorsque les images sont peu contrastées ou lorsqu’il y a des réflexions internes qui biaisent la détection.

Afin de résoudre ces cas complexes qui, encore une fois, nuisent à l’analyse scientifiques, j’ai ajouté la possibilité d’aider le logiciel à détecter les contours, et ainsi à obtenir un image solaire bien ronde:

L’IA à la rescousse

Je suis développeur et en tant que tel, sur ce media, il me semblait pertinent d’ajouter une section sur la façon dont cette version a été développée.

Cette version est la première version qui a été développée avec l’aide de l’IA, en particulier Claude Code. En effet, les dernières innovations en matière d’IA agentique sont pour le coup la véritable révolution à venir : autant avant, avoir une IA qui n’était pas capable de comprendre le contexte, faire des refactorings ou prévoir un plan de développement ne les rendait pas particulièrement utiles, autant les IA à base d’agents, qui sont capables d’analyser votre code, appeler des outils de manière autonome et avoir de vraies interactions avec vous sont un "game changer" de mon point de vue.

Dans cette version, j’ai donc utilisé Claude Code (plan Pro) pour m’aider à faire les refactorings dont j’avais besoin et m’assister dans une tâche où je ne suis pas particulièrement à l’aise : le design d’interfaces graphiques.

De manière générale, ça fonctionne plutôt bien. Très bien même. La capacité de l’outil à définir un plan d’implémentation et comprendre les besoins est assez fascinante. Le code généré, en revanche, nécessite toujours beaucoup de review. On pourrait dire que j’ai l’impression d’avoir un (très bon) stagiaire avec moi, en permanence. En tant que développeur senior, je suis assez rapide à identifier là où l’IA complique les choses inutilement, ou utilise des design pattern dépréciés, ou ne respecte pas les conventions de code. Je serai, par exemple, terrifié si le code original produit était parti en production sans review. Mais, en lui donnant les bonnes directions, en lui expliquant ses erreurs, on arrive rapidement à ce que l’on souhaite avec la qualité que l’on souhaite.

Quelques exemples de choses qui ne fonctionnent pour le coup vraiment pas bien:

-

Claude vous demande de créer un fichier CLAUDE.md qui comprend des instructions sur comment compiler votre projet, comment il est organisé, etc. Bref, du contexte qui est systématiquement ajouté à chaque session. Pourtant, à l’utilisation, Claude ignore allègrement ces instructions.

-

En Java, les fichiers .properties sont encodés en ISO-8859-1, même dans une base où tous les sources sont en UTF-8. C’est une bizarrerie historique, mais Claude ne la comprend absolument pas. A chaque fois qu’il modifie mes fichiers properties (qui servent à l’internationalisation de l’interface), il casse systématiquement l’encodage. Pour l’éviter, le dois systématiquement, avant de lui faire faire une opération dont je sais qu’elle implique ces fichiers, lui dire "respecte les guidelines du fichier CLAUDE" où je lui ai donné une technique pour éviter les problèmes (convertir le fichier en UTF-8, puis l’éditer, puis le reconvertir en ISO-8859-1)

-

Les commentaires dans le code. Quand on commence à avoir un peu de bouteille comme moi, il est assez insupportable de lire des commentaires "captain obvious", ce genre de commentaires qui dit "la ligne suivante calcule 1+1". Claude en génère beaucoup. Trop. Et malgré le fait que mon fichier CLAUDE lui interdise explicitement.

-

La confiance en soi. Claude est bien trop optimiste et tend trop à flatter l’utilisateur. Par exemple, si je lui mens explicitement ("ton algorithme est faux parce que XXX"), il répondra systématiquement "Tu as raison !" sans "réfléchir" (j’utilise les guillemets avec intention), comme un tic de langage ! Ca devient assez frustrant à la longue, lorsqu’il ne comprend pas un problème ou complique inutilement l’implémentation.

-

Les limites : on arrive, sur un projet de la taille de JSol’Ex, très rapidement aux limites d’usage même sur un forfait Pro. Si je suis satisfait de ce que ça m’apporte pour le prix, je ne suis pas prêt à payer les 200€ / mois pour augmenter ces limites. N’oublions pas que je fais ça sur mon temps libre… je n’ai aucune obligation de résultat !

Quoi qu’il en soit, il s’agit là d’avancées qu’il devient difficile d’ignorer. Et ceux qui me connaissent savent à quel point je suis critique sur l’utilisation des IA, les mythes autour de ce qu’elle est capable de faire et son impact écologique. Néanmoins, une chose est certaine : les dirigeants qui pensent économiser du temps et de l’argent en virant leurs développeurs pour les remplacer par de l’IA se mettent une balle dans le pied : elle pose de sérieux problèmes de qualité de code et donc de maintenance, et, avec l’arrivée des agents, posent de graves problèmes de sécurité (un outil autonome qui décide par lui même s’il faut vous demander l’autorisation pour exécuter une commande !"). L’IA doit être vue comme une aide à la productivité, mais qui doit être cadrée par des gens d’expérience. Bref, nous sommes à un tournant et je ne suis pas encore bien à l’aise avec ce que cela implique. Nous n’avons jamais été aussi près du rêve de gosse que j’avais d’IA "autonomes", mais la maturité me force à en avoir peur.

Mais nous nous éloignons là du sujet initial et concluons donc ce billet : dites bienvenue à JSol’Ex 4, consultez la vidéo de présentation ci-dessous et n’hésitez pas à contribuer !

Ellerman Bombs Detection with JSol’Ex 3.2

17 May 2025

Tags: solex jsolex solar astronomy ellerman bombs

About Ellerman Bombs

Ellerman bombs were first described by Ferdinand Ellerman back in 1917. Ellerman’s article was named -Solar Hydrogen "Bombs"- and it’s only later that these were commonly referred to as "Ellerman bombs".

I came upon this term while reading an article from Sylvain or André Rondi quite early in my solar imaging journey, and I was since then obsessed by these phenomena.

Ellerman Bombs are small, transient, and explosive events that occur in the solar atmosphere, particularly in the vicinity of sunspots. These are very short lived compared to other solar features: from several dozens of seconds to a few minutes. The most common explanation is magnetic reconnection, which occurs when two magnetic regions opposite polarity come into contact and reconnect, releasing energy in the form of heat and light. This is for example described in this article from González, Danilovic and Kneer.

Amateur observations of Ellerman bombs are quite rare, but Rondi described such observations using a spectroheliograph back in 2005. They are rare because they are mostly invisible where the amateur observations are made (the center of the H-alpha line), and are too small to notice. However, these are visible in the wings of the H-alpha line: this is where a spectroheliograph comes in handy, since the cropping window that is used to capture an image contains more than just the H-alpha line.

I had a long standing issue to do something about it in JSol’Ex, and I finally got around to it: all it took was getting some test data to entertain the ideas.

Observation of an Ellerman Bomb

I am doing many observations of the sun: I started in 2023 with a Sol’Ex, then I recently got an SHG 700, so I have accumulated quite a bit of data, which is completed by scans which are shared with me by other users of JSol’Ex.

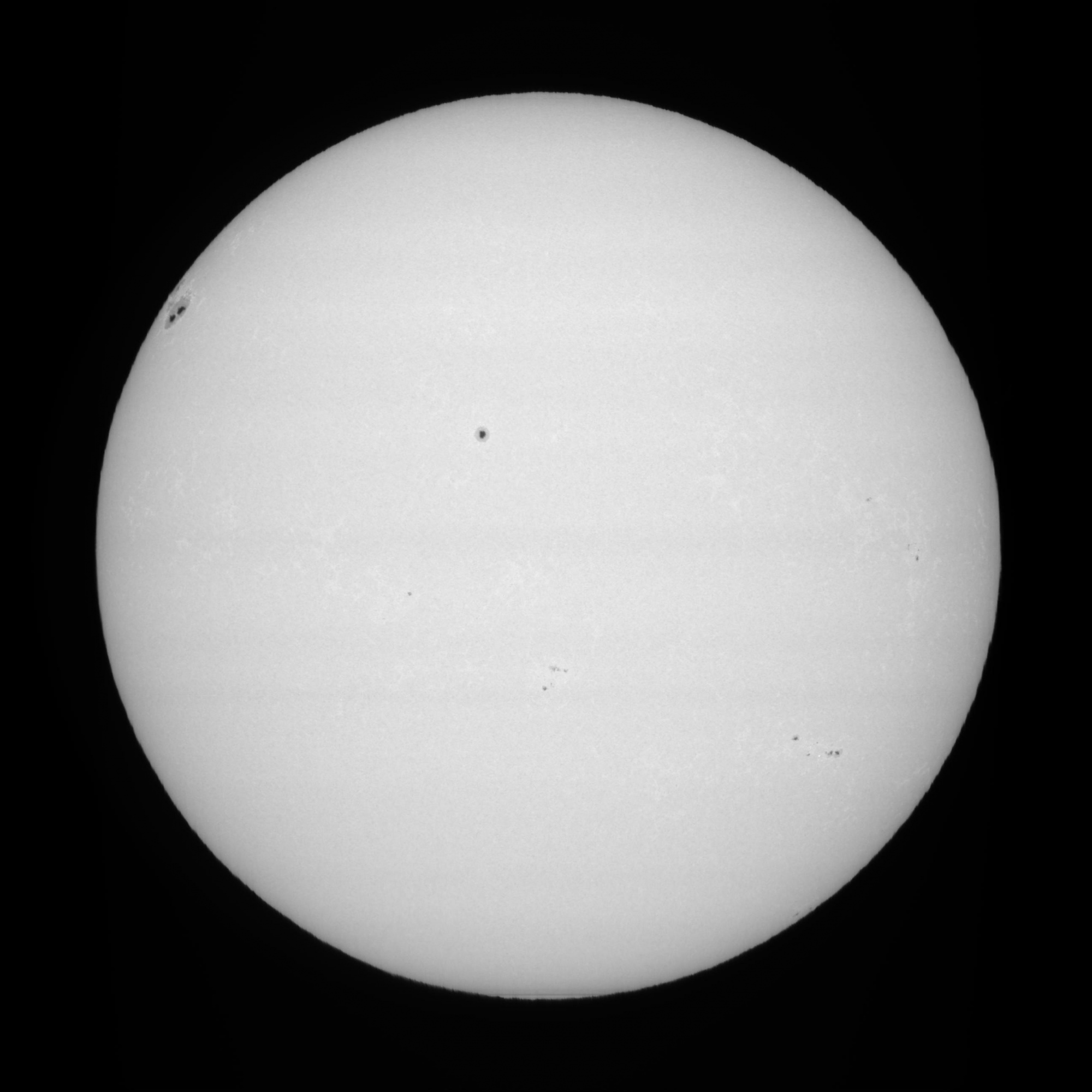

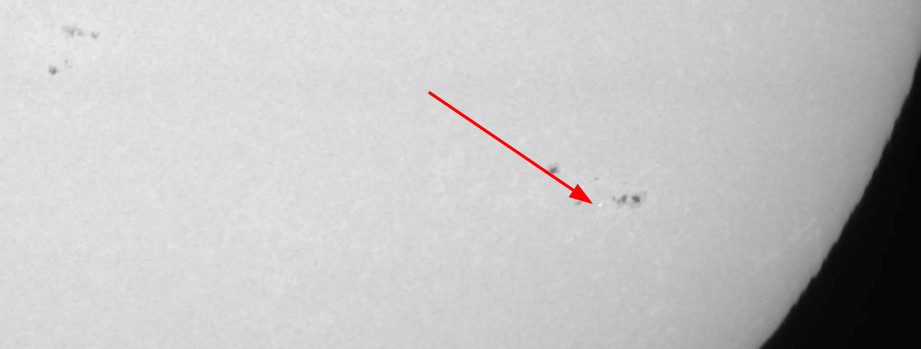

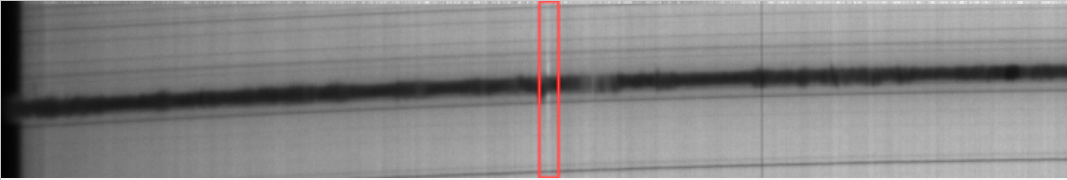

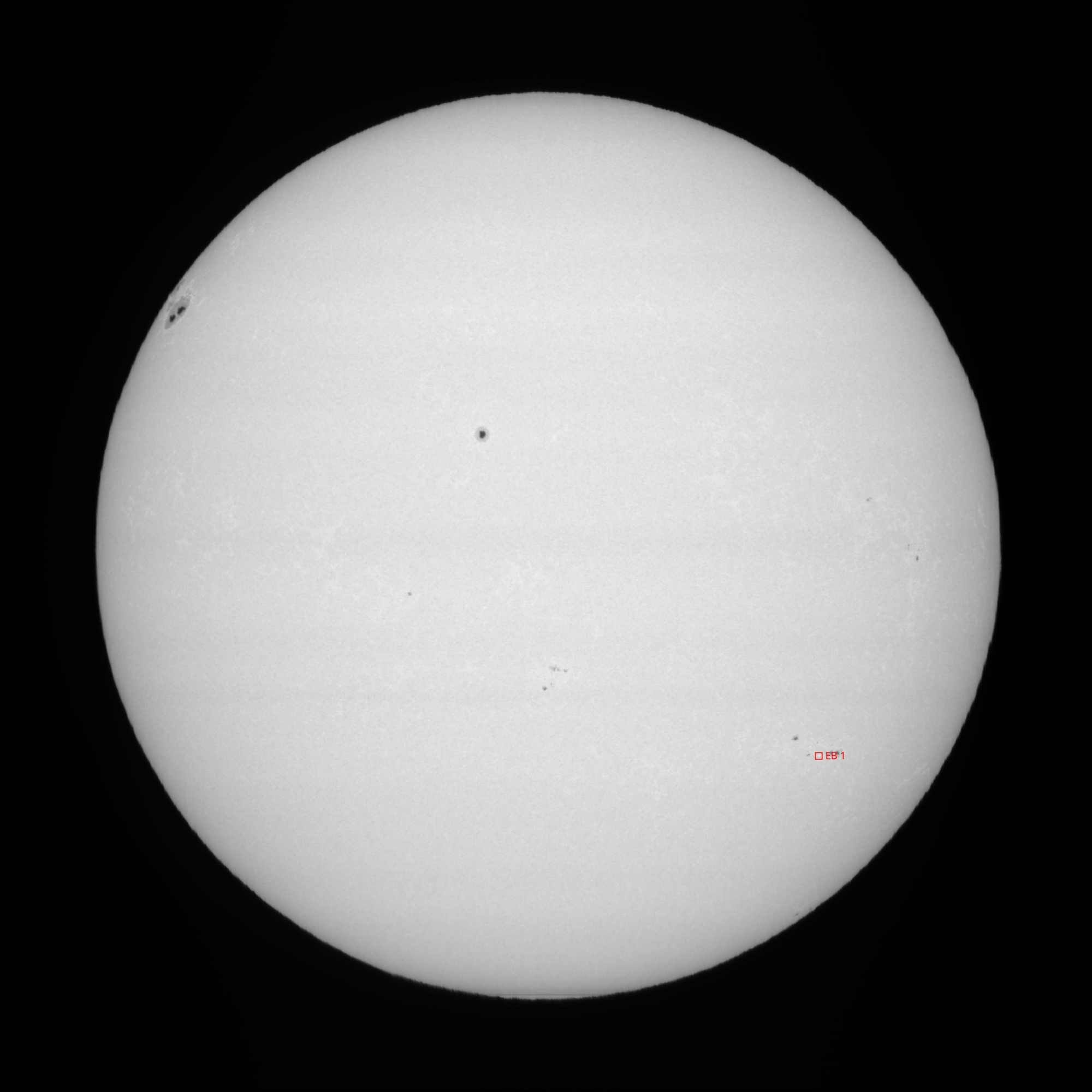

I have been looking for Ellerman bombs in my data, but I never found any yet. This changed a couple weeks ago: I was doing some routine work on JSol’Ex and using a capture I had done in April, 29, 2025 at 08:32 UTC, when I noticed, by accident, a bright spot in the continuum image:

It may not be obvious at first, which is precisely why these are hard to spot, so here’s a hint:

JSol’Ex offers the ability to easily generate animations of the data captured at different wavelengths, so I generated a quick animation, which shows the same image at ±2.5Å from the center of the H-alpha line:

We can see the typical behavior of an Ellerman bomb: it is bright in the wings of the H-alpha line, but it vanishes when we are at the center of the line. The fine spectral dispersion of the spectroheliograph makes it possible to highlight this phenomenon very precisely.

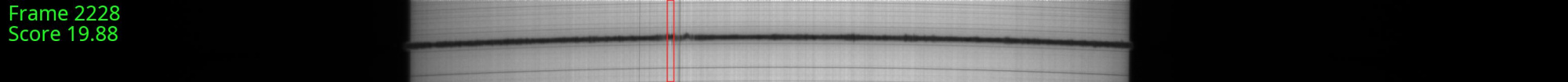

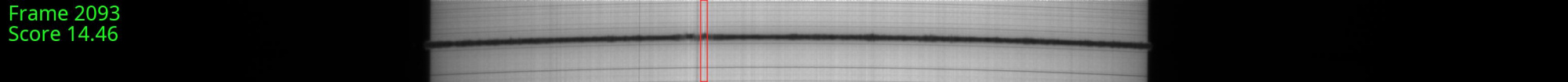

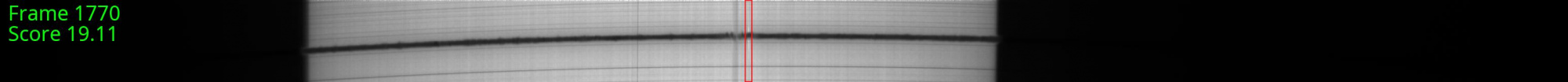

The corresponding frame of the SER file shows the aspect of the Ellerman bomb in the spectrum:

The shape that you can see is often referred to as the "moustache". At this stage I was pretty sure I had observed my first Ellerman bomb, and that I could implement an algorithm to detect it.

JSol’Ex 3.2 auto-detection

JSol’Ex 3.2 ships with a new feature to automatically detect Ellerman bombs in the data. Currently, it is limited to H-alpha, but it should be possible to detect these in CaII as well.

The algorithm I implemented uses statistical analysis of the spectrum to match the characteristics of the "moustache" shape, in particular:

-

a maximum of intensity around 1Å from the center of the line

-

a distance which spreads up to 5Å from the center of the line

-

a brightening which is only visible in the wings of the line

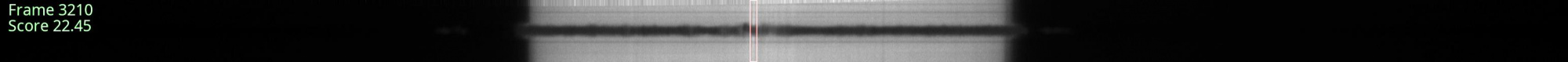

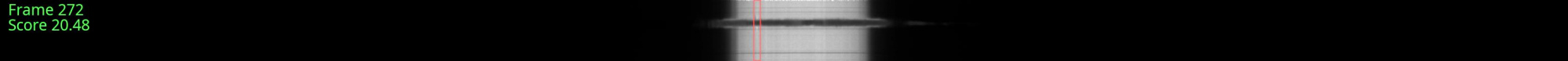

JSol’Ex will generate, for each detection, an image showing the location of the detected bombs:

And for each bomb, it will create an image which shows the region of the spectrum which is used to detect the bomb. This is for example what is automatically generated for the bomb described above:

Algorithm details

|

Note

|

This is a description of the algorithm that I implemented in an adhoc fashion: I’m not a mathematician nor a scientist: I’m an engineer and the algorithm above was implemented using my "intuition" of what I thought would work. It is likely to change as new versions are released. |

The algorithm is based on the following steps:

-

for each frame in the SER file, identify the "borders" of the sun

-

perform a Gaussian blur on the spectrum to reduce noise

-

within the borders, compute, for each column, the average intensity of the spectrum for the center of the line and the wings separately. The center of the line is defined as the range [-0.35Å, 0.35Å] and the wings as the range [-5Å, -0.35Å[ ∪ ]0.35Å, 5Å]

-

compute the maximum intensity of the wings, starting from the center of the line, and going outwards until we reach the maximum intensity (local extremum)

-

compute the average of each column average intensity for the wings (the "global average")

With Ellerman bomb scoring parameters defined below, the algorithm proceeds per column:

-

For each column index

xin the spectrum image: -

Build a neighborhood of up to 16 columns around

x:Nₓ = { x + k | k ∈ ℤ, |k| ≤ 8 }, clamped to the image boundaries. -

Compute the overall mean column intensity

Ī_global = (1 / N_total) ∑_{j=1..N_total} Ī(j). -

Exclude any columns in

Nₓwhose average intensity falls below 90 % ofĪ_global, since very dark columns (usually sunspots) would pull down our estimate of the local wing background and hide true brightening events. Call the remaining setMₓand letm = |Mₓ|. -

If

m < 1, there aren’t enough valid neighbors to form a reliable background—skip columnx. -

On the Gaussian-smoothed data, measure three key values at column

x: -

c₀ ≔ I_center(x), the mean intensity in the core region of the spectral line. -

c_w ≔ I_wing(x), the average intensity across the two wing windows at ±1 Å. -

c_max ≔ max_{p ∈ wing-pixels nearest ±1 Å} I(p, x), the single highest wing intensity near the expected shift. -

Compute the local wing background

r₀ = (1 / (m−1)) ∑_{j ∈ Mₓ, j≠x} I_wing(j). Using only nearby “bright enough” columns keeps the background estimate from being skewed by dark features. -

Define a line-brightening factor

B = max(1, c₀ / min(r₀, I_center,global)). Ellerman bombs boost the wings without greatly brightening the core, whereas flares brighten both. -

Form an initial score

S₀ = 1 + c_max / min(r₀, I_wing,global), whereI_wing,global = (1/N_total) ∑_{j=1..N_total} I_wing(j). This compares the local wing peak to the typical wing level across the image. -

Adjust for how many neighbors were used:

S₁ = S₀ × (m / 16). Fewer valid neighbors mean less confidence, so the score is scaled down proportionally. -

Compute the wing-to-background ratio

rᵢ = c_max / r₀. Ifrᵢ ≤ 1.05, the wing peak is too close to the local background and the column is discarded. Otherwise, we boost the score further: -

Raise

S₁to the power ofe^{rᵢ}, givingS₂ = S₁^( e^{rᵢ} ). This makes the score grow quickly when the wing peak stands out strongly. -

Multiply by

√(c_max / c₀)to getS₃ = S₂ · √(c_max / c₀). That emphasizes cases where the wings are much brighter than the core. -

Finally, penalize any shift away from the ideal ±1 Å wing position. If

y_coreandy_maxare the pixel locations of line center and wing peak, computeΔλ = |y_max – y_core| × (Å / pixel), thenS_final = S₃ / (1 + |1 Å – Δλ|). -

If

S_final > 12, mark columnxas a candidate event. Use the value ofBto decide: -

When

B < 1.5, it behaves like an Ellerman bomb (wings bright, core unchanged). -

When

B > 2, it matches a flare (both core and wings bright). -

If

1.5 ≤ B ≤ 2, the result is ambiguous and ignored.

All thresholds (0.9× global mean, 1.05 ratio, score > 12, B cutoffs) were chosen by testing on data and visually inspecting results.

Post-filtering

There will often be cases where the same bomb is detected in multiple frames. Therefore, we need to do some merging of bombs which are spatially connected.

Eventually, we apply a limit threshold: if there are more than 5 Ellerman Bombs detected in an image, then we consider the detection to be false positives (this happens typically on saturated images, or images with too much noise). This is a bit arbitrary, but it seems to work well in practice.

Test data

I had about ~1100 scans I could reuse for detection, and it successfully discovered Ellerman bombs candidates in about 10% of them. Of course this required some tuning and several runs to get the parameters right. This doesn’t mean that you have 10% chances of finding an Ellerman bomb in your data, because the test data I have is biased (I often do 10 to 20 scans in a row, within a few minutes, to perform stacking, so if a bomb is detected in an image, it has decent chances of being detected in the next one). Also, I am using the term "Ellerman Bomb candidate", because there’s nothing better than visual confirmation to make sure that what you see is indeed an Ellerman bomb: an algorithm is not perfect, and it may fail for many reasons (noise, saturation, artifacts, etc.)

Here are a few examples of Ellerman bombs candidates detected in my data:

Conclusion

This blog post described my first visual Ellerman bomb detection. Then I described how I implemented an algorithm to automatically detect Ellerman bombs in JSol’Ex 3.2. I am very happy to release this to the wild, so that this kind of discovery is made more accessible to everyone. Of course, as I always say, you should take the detections with care, and always review the results. This is why you get both a global "map" of the detected bombs, and a detailed view of each bomb, which can be used to confirm the detection. In addition, I recommend that you create animations of the regions, which you can simply do in JSol’Ex by CTLR+clicking on the image then selecting an area around the bomb.

Finally, I’d like to thank my friends of the Astro Club de Challans, who heard me talk about Ellerman bombs detection for a while, showing them preliminary results, and who were very supportive of my work. Last but not least, thanks again to my wife for her patience, seeing me work on this (too) late at night!

Bibiography

Jagged Edges Correction with JSol’Ex 3.1

02 May 2025

Tags: solex jsolex solar astronomy

I’m happy to announce the release of JSol’Ex 3.1, which ships with a long awaited feature: jagged edges correction! Let’s explore in this article what this is about.

The dreaded jagged edges

Spectroheliographs like the Sol’Ex or the Sunscan are not using a traditional imaging system like, for example, in planetary imaging, where you can capture dozens to hundreds of frames per second and do the so called "lucky imaging" to get the best frames and stack them together to get a high resolution image.

In the case of a spectroheliograph, the image is built by scanning the solar disk in a series of "slices" of the sun: it takes several seconds and sometimes minutes (~3 minutes when you let the sun pass "naturally" through the slit) to get a full image of the sun.

In practice, this means that between each frame, each "slice" of the sun, the atmosphere will have slightly moved, causing some misalignment between the frames. This is also particularly visible when there is some wind, which can cause the telescope to shake a bit, and the image to be misaligned. Lastly, you may even have a mount which is not perfectly balanced, or which has some resonance at certain scan speeds.

As an illustration, let’s take this image captured using a Sunscan (courtesy of Oscar Canales):

This image shows 3 problems:

-

the jagged edges, which cause some unpleasant "spikes" on the edges of the sun

-

misalignment of features of the sun, particularly visible on filaments

-

a disk which isn’t perfectly round

These issues are typical of spectroheliographs, and are the main limiting factor when it comes to achieving high resolution images. Therefore, excellent seeing conditions are a must to get high quality images. Even if you do stacking, the fact that the reference image will show spikes is often a problem.

Correcting jagged edges

Starting with release 3.1.0, JSol’Ex ships with an experimental feature to correct jagged edges. It is not perfect yet, but good enough for you to provide feedback and even improve the quality of your images.

For example, here’s the same image, but with jagged edges correction applied:

And so that it’s even easier to see the difference, here’s a blinking animation of the two images:

The jagged edges are now mostly gone, the features in the sun are better aligned, and the image is much more pleasant to look at. There is still some jagging visible, the correction will never be perfect, but it is a good start.

In particular, you should be careful when applying the correction, because it could cause some artifacts in the image, in particular on prominences. As usual, with great powers comes great responsibilities!

How does it work?

To illustrate how the correction works, let’s imagine a perfect scan: a scan speed giving us a perfectly circular disk, no turbulence, no wind, etc.

In this case, what we would see during the scan is a spectrum which width slowly increases, reaches a maximum, and then decreases. The pace at which the width increases and decreases is determined by the scan speed and is predictable. In particular, the left and right borders of the spectrum will follow a circular curve.

Now, let’s get back to a "real world" scan. In that case, the left and right edges will slightly deviate from the circular curve. They will also follow the path of an ellipse: in fact, this ellipse is already required in order to perform geometric correction.

The idea is therefore quite simple in theory: we need to detect the left and right edges of the spectrum, then compare them to the ideal ellipse that we have computed. Pixels which deviate from this curve give us an information about the jagged edges. We can then compute a distortion map, which will be used to correct the image.

In practice, we also need to apply some filtering of samples: in practice, while the detection of edges is robust enough to provide us with a good geometric correction, it is not perfect. It can also be skewed by the presence of proms for example. Therefore, we are performing a sigma clipping on the detected edges, in order to remove outliers, that is to say pixels which deviate too much from the average deviation.

This is also why the correction will not work properly if the image is not focused correctly: you would combine two problems in one, and the correction would not be able to detect the edges properly.

In addition, in the image above you can see that the bottom most prominence is slightly distorted, which is caused by the fact that it’s far away from the 2 points which were used to compute the distortion. It may be possible to reduce such artifacts by using a smaller sigma factor (at the risk of undercorrecting edges).

Conclusion

In this blog post, I have described the new jagged edges correction feature in JSol’Ex 3.1. This solves one of the most common issues users are having with spectroheliographs, and I hope it will help you get better images. However, as usual, it’s a work in progress, so do not hesitate to provide feedback!

Older posts are available in the archive.