Dependency Management at Gradle

11 July 2019

Tags: gradle dependency management

Opinions are my own, not those of my employer

I joined Gradle 4 years ago, and I spent the last 2 years almost exclusively working on dependency management. The more I work on this topic, the more I am frustrated by the state of our industry. In this blog post I will mostly illustrate my points with Java, which I’m mostly familiar with, but a lot of them stand true whatever the ecosystem (Javascript, Python, Go, …).

Soon, we should release Gradle 6 (fall 2019, no promise, as always, this is software). This version will be the first one to turn the spotlights on dependency management. This will be for me the achievement of 2 hard years of work (not alone, of course) but this is just the beginning. Gradle probably has the most advanced dependency engine of the market (forgive me if I’m wrong, let me know). But what makes it so different is not that it has powerful features like dependency substitution, customizable resolution, dependency locking, alignment, etc… No, what makes it different it’s that we put a lot of emphasis on semantics: model software correctly so that you, as a developer, have less to handle.

Often, folks "from the outside" are considering us arrogant, because we don’t immediately support things that other engines do (eg. "you don’t want to implement optional dependencies, look, Maven has it for years you s***"). While I understand the frustration, it doesn’t mean that we don’t hear. In fact, we hear you loud, but the time it takes to land is just the consequence of willing to implement the correct solution to a problem.

For example, what does an optional dependency mean? A few months ago, I read this from the Yarn documentation which got me scared, and, to be honest, a bit despaired too:

This looks like total non-sense to me. Because we needed the infrastructure, it took some time but we implemented what we think is a better solution. In a nutshell, optional dependencies are not optional. They are things that you need if you use a particular feature of a library. So it means that if you depend on something, and that this something has optional features, you can say what features you need and Gradle would give you the correct dependencies for this. We called that feature variants. Granted, the name isn’t cool, but it’s a matter of time until we refactor the documentation to make it easier to discover.

Similarly, we implemented back in Gradle 3.4 the separation of API and implementation dependencies for the Java world.

In fact, that’s one of the reasons the compile configuration has been "soft deprecated" for years now, and that we’re going to nag you starting from Gradle 6.

I still hear people claiming they don’t need this and that it’s hard to understand but I stand by the fact they deperately need them.

Why is it important? Because if you are a library author, you know that there are things that are "your internal sauce": things which are implementation details, not part of the public API, and that should never be exposed to consumers.

This is the very reason Java 9 shipped with the module system: strong encapsulation.

However, how does it work for dependencies? There are also dependencies which are part of your API and others which are not.

Say you use Guave internally. None of the Guava classes are visible on your public API, and it would be an error to do so.

Then it means that Guava is an implementation dependency of your library.

When you do this, you should be allowed to replace Guava with something else at any time, without breaking any of your consumers.

The horrible reality is that if you use the Maven <compile> scope, those dependencies are going to leak to the consumers, and they could accidentally start using Guava just because it’s available on the classpath (yeah, IDEs love this, the class is available for completion you know!).

This is a problem with Maven because the POM file is used for 2 distinct purposes:

-

representing the point of view of the producer, where

<compile>means "I need this on my compile classpath" -

representing the point of view of the consumer, where

<compile>semantics are there broken: it means "add this to your compile classpath", but it means you leak dependencies which should have been on the<runtime>scope!

With the Gradle Java Library plugin, those issues go away: we model those correctly, and when we generate a POM file, it has dependency declarations which make sense for the consumer. I’ve been battling to explain this in conferences for years, yet, lots of people don’t get how harmful to the whole ecosystem that design decision from Maven was: it just prevents smooth dependency upgrades, and contributes to the "classpath explosion".

In other words, you, as a developer, should always know what you directly use (your first level dependencies).

As another example, we’ve been yelling for years how bad exclusions are, but we did a really bad job at explaining why. The problem is also that we didn’t have all the tools we needed to workaround them, so we said "yeah it’s bad" but didn’t really say that you can still use them in some cases.

In a nutshell, an exclusion is bad because the dependency resolution engine doesn’t know why you excluded a dependency:

-

is it because the producer had bad metadata, that the dependency should have been "optional", or just absent altogether?

-

is it because you don’t use a specific code path of a dependency and you just want to slim down the size of your distribution?

-

is it because something breaks if you use this dependency?

-

is it because it’s yet another logger on the classpath and this is not the one you use?

Well, again, for all those use cases, the solutions are different. The logging use case is an illustration of this: how many of you have faced this infamous problem of having multiple SLF4J bindings on the classpath? How do you fix that with Maven? Exclude of course!

But wouldn’t it better if you could express that "between all those logger bindings, this is the one I choose". Wouldn’t it better if, as a producer of a logger binding, you could say "I implement this logger API, and it doesn’t make sense to have multiple logger bindings on the classpath at the same time". Well, this is what Gradle offers you, as a producer and as a consumer.

Modeling software is important, because it makes the industry better as a whole. By explaining why instead of how, the dependency management engine can take better decisions. It can fail if things are incompatible, it can ask you to choose between different implementations.

Do you need another example? Look at all those "Maven classifiers". How many times did you got multiple conflicting implementations of the same thing just because they had different classifiers (looking at you, Guava!).

The reality is that a classifier is a workaround for a bad model, incapable of expressing that you have different things published at the same coordinates. Sometimes I read comments like "Gradle is just Maven with a Groovy DSL". This is wrong at so many levels: Gradle empathizes on strong modelling of software. We need to think in terms of components ("this is a library", "this is a Boot application", "this is a Gradle plugin"), not in terms of conventions. Models are orthogonal to conventions: conventions are just a tool to make modelling easier to implement, but what matters is the model. The DSL also doesn’t matter: Groovy, Kotlin, whatever. What makes Gradle powerful is that it understands what you build.

This is one of the reasons we came with Gradle Module Metadata, which is going to be enabled by default in Gradle 6.

We, at Gradle, think that we can save a lot of developer time by simply putting more sense in those things we publish. It’s a waste of time and energy that we all have to fix, constantly, those conflicts between libraries.

And can we talk about ethics? It’s beyond me we can tolerate, as developers/engineers, repeated approximations, errors, just because Maven does it this way? I don’t really care that we’re not compatible with Maven, as long as we solve the problem and that we move towards well designed, better solutions. Sometimes we have to make tradeoffs, but we can’t compromise on reproducibility, correctness and performance. Of course, we do our best to provide Maven compatibility, and again, sometimes make it even better in some situations (the Java Library plugin).

My goal is that we, as a whole, move towards a better software delivery world.

The good thing is that what we’re not alone. This, is the result of years of experience from the team with very large builds, from customers of small to very large organizations, and discussions with talented open-source developers (special thanks from me to Andy Wilkinson from the Spring team).

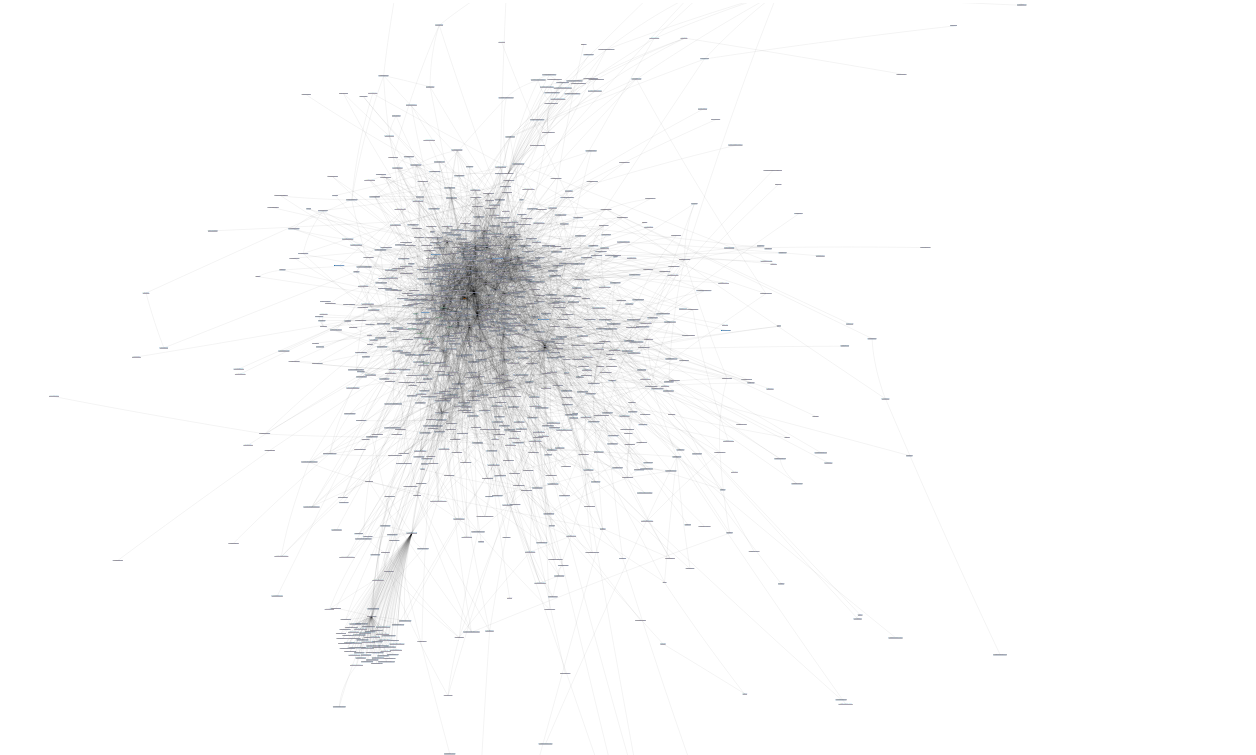

I posted this earlier this month on Twitter, this is a real dependency graph, from an organization I have the opportunity to work with:

This is not uncommon, this is the reality we live in.

And when you have such a dependency graph, you desperately need more modelling. Does it mean that Gradle is perfect? Hell, no. We’re going to make mistakes, we already have and we will continue, but what matters is that we’re moving towards our goal.

There are lots of good things coming in Gradle 6, stay tuned. In the meantime, a lot of what I discussed here has been presented in a couple of webinars:

Another webinar is planned after summer, around multi-repository development.

Hope you’ll enjoy!