Partial Eclipse of March 29, 2025

30 March 2025

Tags: solex jsolex solar astronomy

In this blog post I’m describing what is probably a world premiere (let me know if not!): capturing a partial solar eclipse using a spectroheliograph and making an animation which covers the whole event.

Edit: Turns out Olivier Aguerre did something similar, described here (french).

Preparations

On March 29, 2025, we were lucky to get a partial solar eclipse visible in France, with a maximum of about 25%. I wanted to do what was a first for me, capturing the event, so I used a TS-Optics 80mm refractor with a 560mm focal length, equipped with an MLAstro SHG 700 spectroheliograph. The Astro Club Challandais was organizing a group observation this morning, but my initial decision was not to attend. Instead, I opted to limit the risks by performing this somewhat complex setup at home, in familiar territory. Unlike the SUNSCAN, using a spectroheliograph like the SHG 700 requires more equipment: a telescope, a mount (AZ-EQ6), and in my case, a mini PC for data acquisition (running Windows) along with a laptop for remote connection to the PC.

I have conducted observations away from home before, but from experience, setting everything up—including WiFi, polar alignment, etc.—can be a bit too risky for an event like this. So, all week, I anxiously monitored the weather. Yesterday, the forecast looked grim, with thick clouds and rain. However, the gods of astronomy were merciful, blessing us with a beautiful day. The sky wasn’t entirely clear, but it was good enough for observations.

Some more context

First of all, I had a specific observation protocol in mind. As you may know, a spectroheliograph doesn’t directly produce an image—it requires software to process video scans of the Sun. In the case of the Sunscan, the software is built into the device, but for a Sol’Ex-type setup, an independent software handles this task. You are probably familiar with INTI, but I have my own software: JSol’Ex.

The advantage of developing my own software is that I was able to anticipate potential issues. One major challenge with an eclipse is that the software must "recognize" the Sun’s outline, which won’t always be perfectly round—in fact, it could be quite elliptical. The software corrects the image by detecting the edges, but when the Moon moves in front, the sampling points become completely incorrect, sometimes detecting the lunar limb instead of the Sun’s!

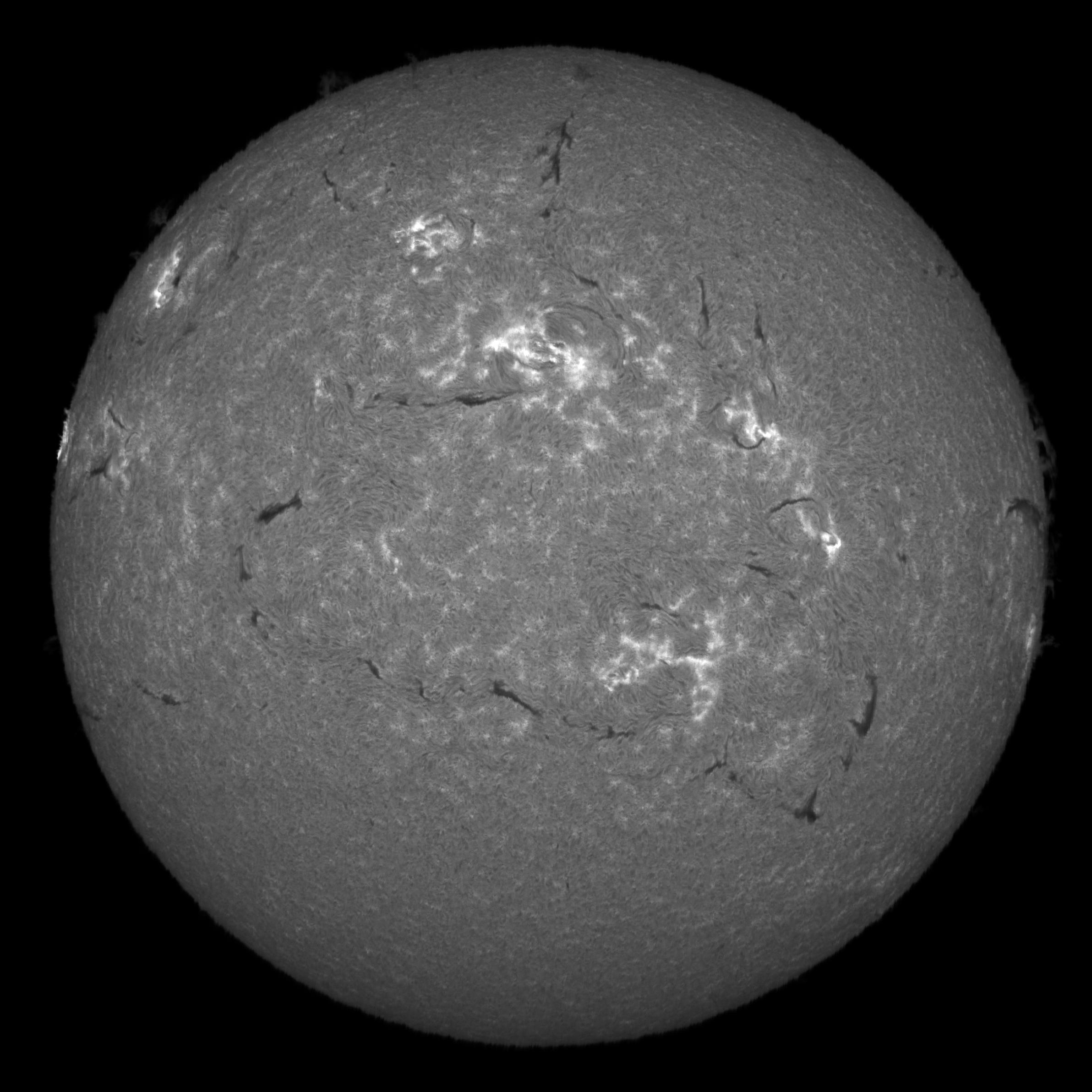

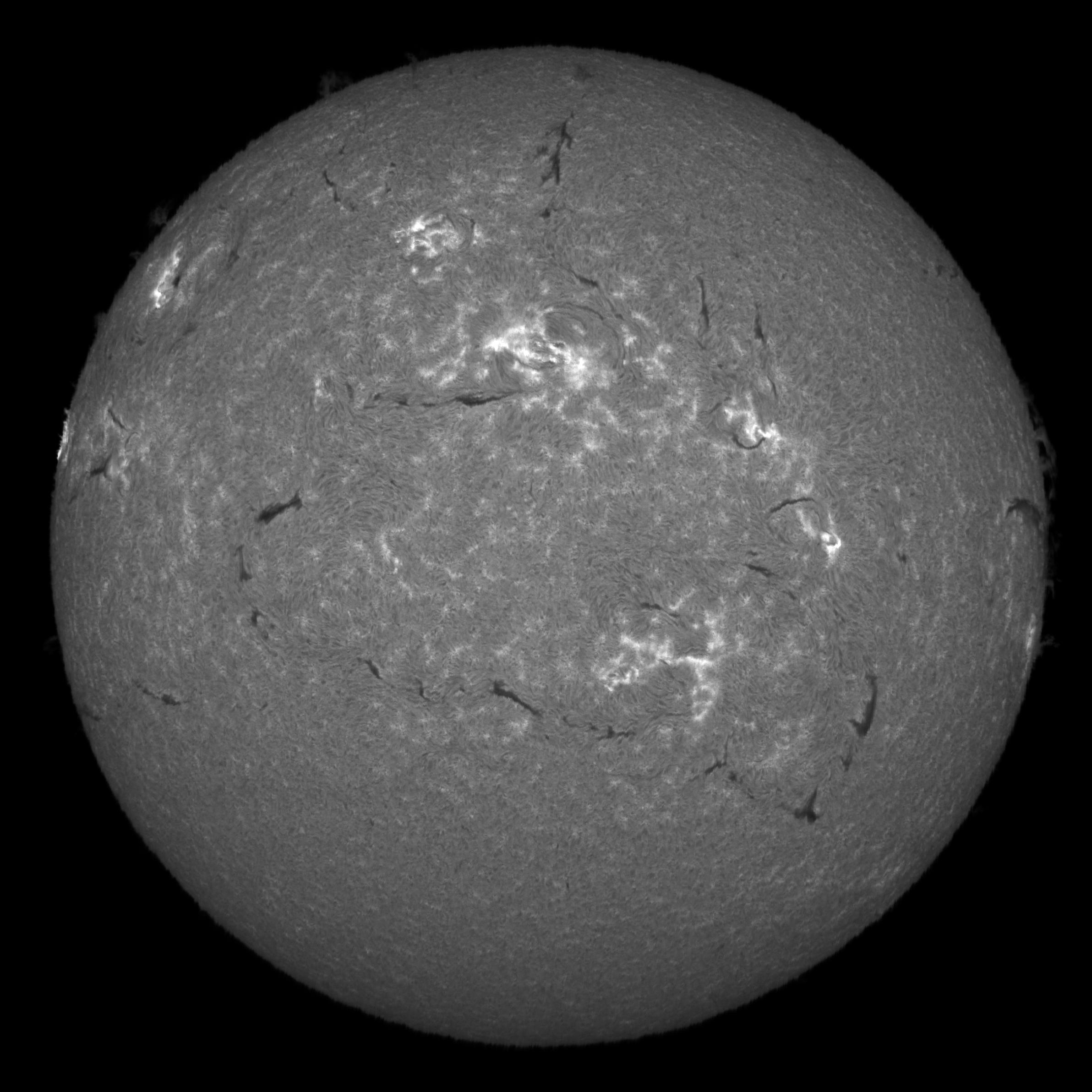

My strategy was to start early enough to adjust settings for minimal camera tilt and, more importantly, to ensure an X/Y ratio of 1.0. With these reference scans, I could then force all subsequent scans to use the same parameters. So, I began my first scans under a beautifully clear sky! After some adjustments, I was ready: a single scan, and we were good to go!

At the same time, I activated JSol’Ex’s integrated web server and set up a tunnel so my friends could watch my observations live! I planned to perform a scan every two minutes using a Python script in SharpCap, automating the recording, scan start, stop, and rewind. JSol’Ex’s "continuous" mode processed scans in real time. Everything was going smoothly… until panic struck—clouds!

For the past three hours, the sky had been perfectly clear. Yet, just ten minutes before the eclipse began, clouds started rolling in. What bad luck! Fortunately, by spacing out the scans, I managed to capture many of them in cloud-free moments.

The eclipse began, and the first scans featuring the Moon appeared. It worked! Forcing the X/Y ratio was effective!

As the scans piled up, I encountered a new problem. While locking the X/Y ratio helped, the software still needed to calculate an ellipse to determine the Sun’s center for cropping. But things started going wrong—the software was miscalculating everything. I had anticipated this, and I already had a workaround in mind, but the necessary code wasn’t deployed on my mini PC. So, I didn’t worry too much and simply shared the raw images, which were perfectly round—because, as you recall, I had already adjusted my X/Y ratio to 1.0!

I continued scanning, though my setup wasn’t perfectly precise. My polar alignment wasn’t flawless, and I had no millimeter-accurate return-to-start positioning. As a result, I had to manually realign between each scan. While this wasn’t a major issue, it did create some intriguing scans. For those familiar with Sol’Ex, seeing "gaps" in the spectrum due to the Moon’s presence was quite unusual, making centering more difficult.

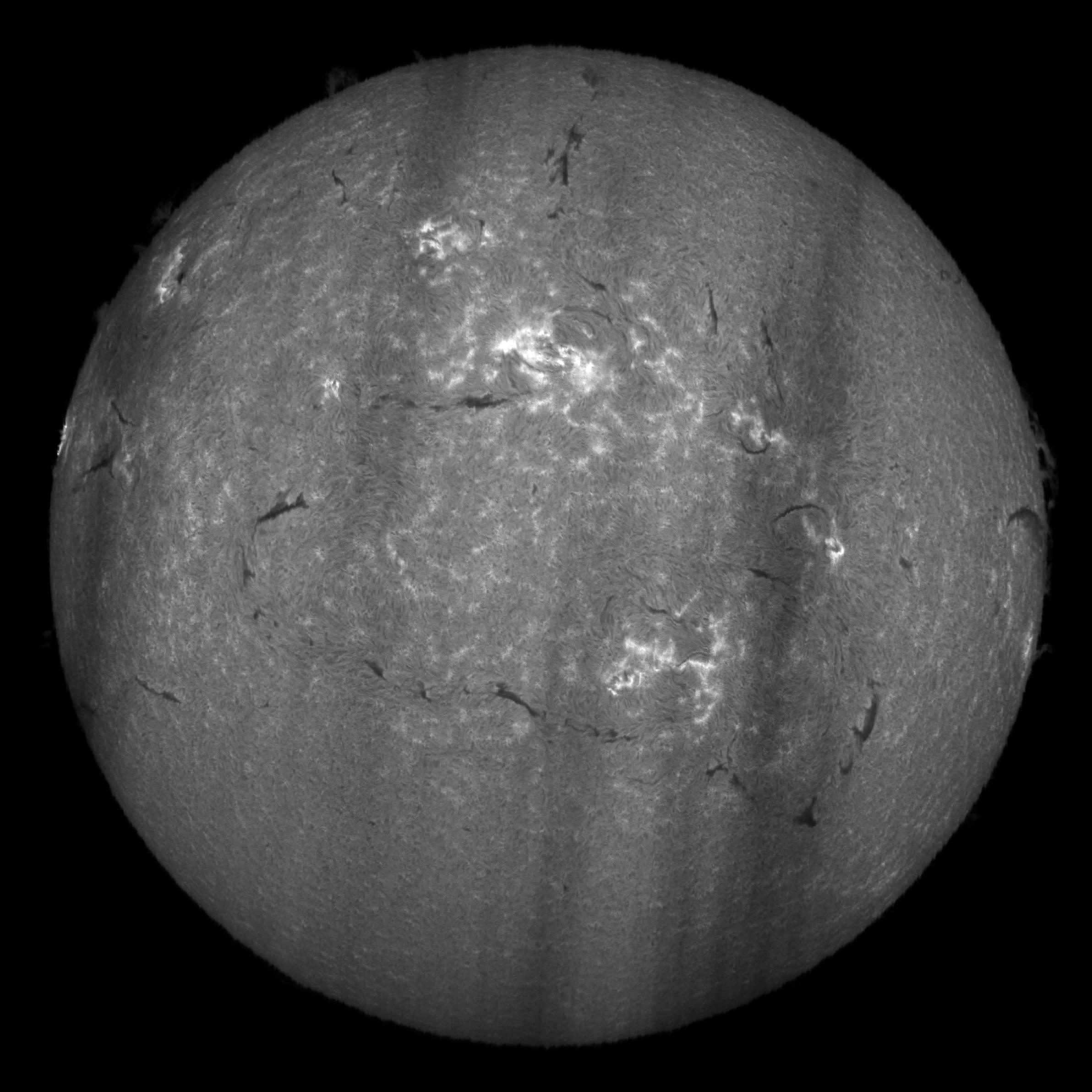

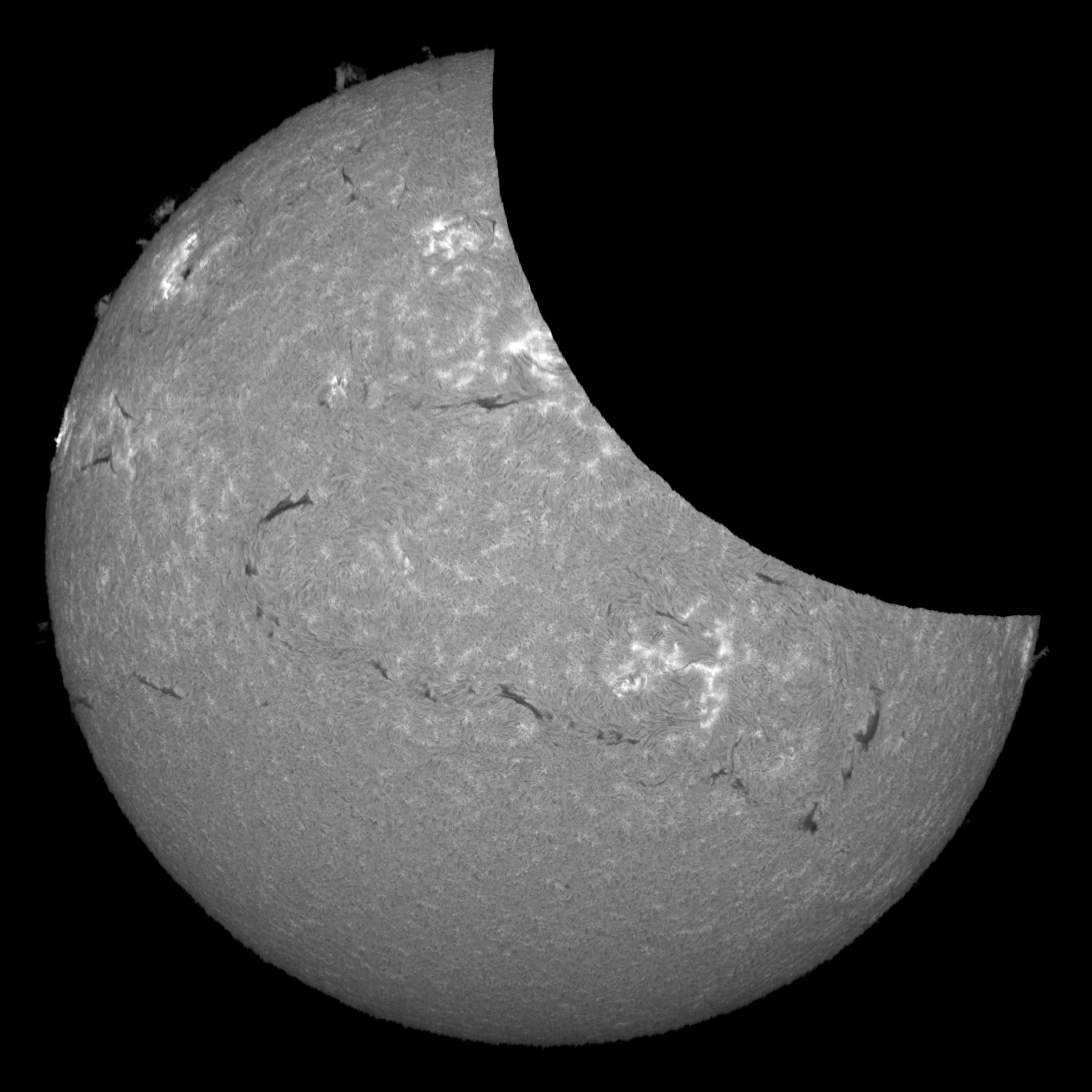

The eclipse reaches maximum

Time passed, scans continued, and finally, we reached the maximum eclipse phase!

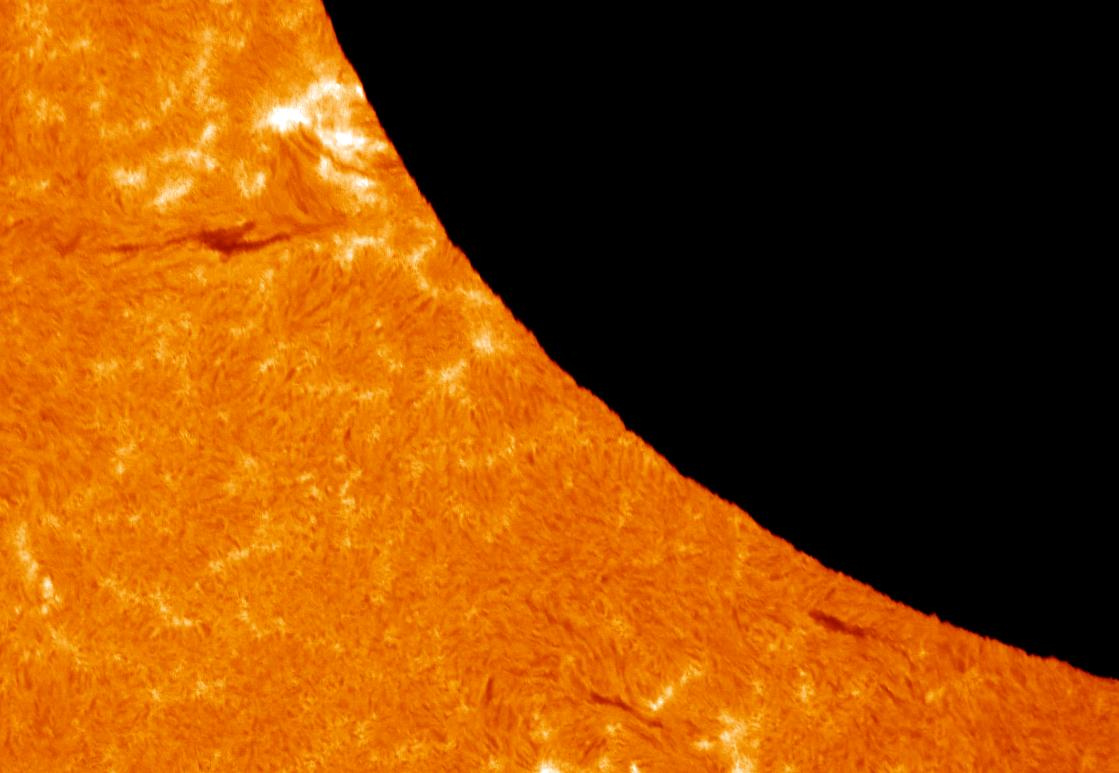

At one point, I wondered whether we could see lunar relief in the images. However, given the jagged edges typical of SHG imaging, it was hard to say for sure, but, I think some of the details visible below are actual surface details.

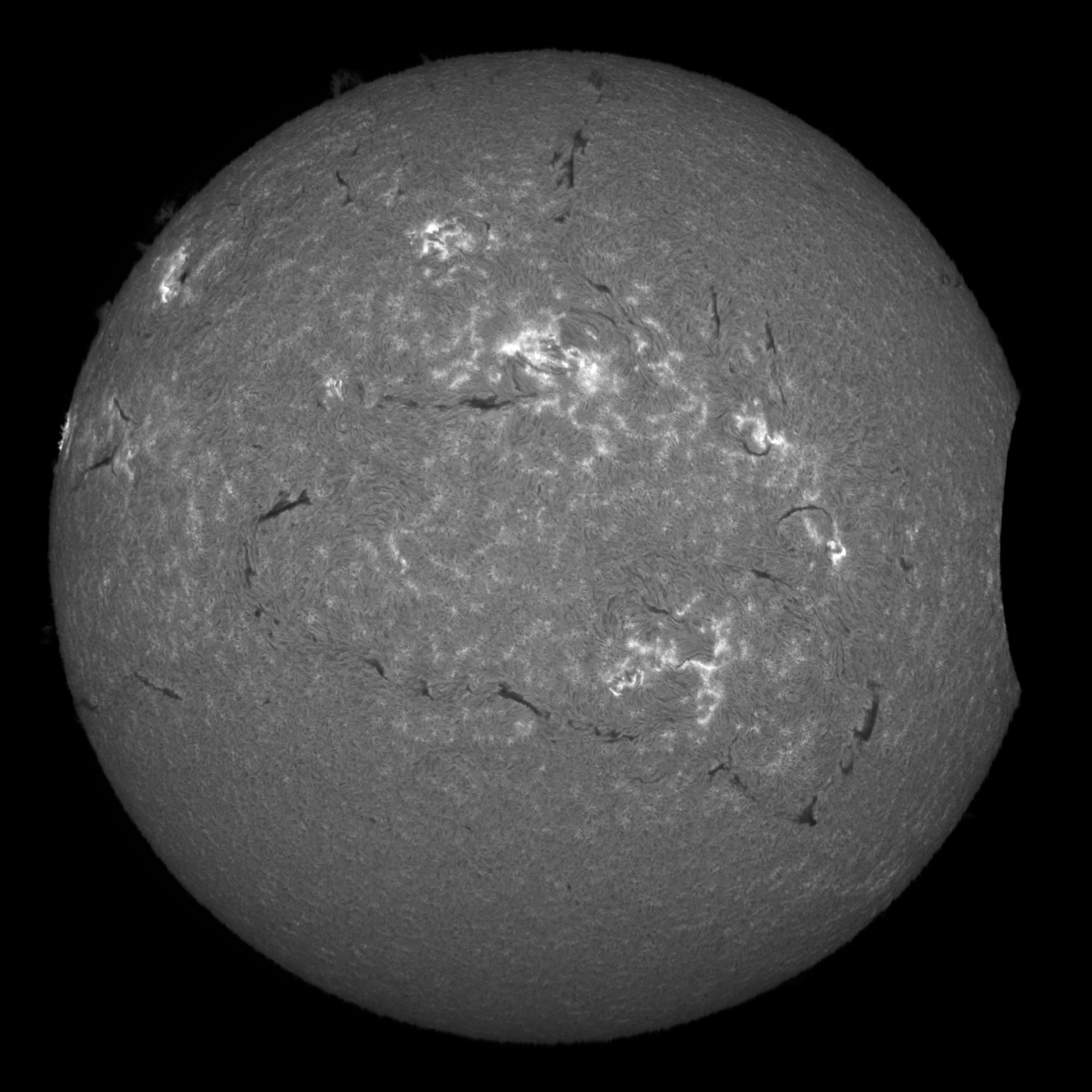

End of observation

By the end of the eclipse, I had 80 SER files, taken between 9:37 AM and 1:43 PM, totaling nearly 175 GB of data! It was time to transfer everything to my desktop PC to create an animation. This also gave me a chance to test whether my earlier workarounds for ellipse detection would function as expected. I ran batch processing, and boom—within minutes, I had this animation:

And here’s the continuum version which was weirdly compressed by Youtube:

This was just a first draft, using a beta version of my software. A few hours later I released a new version of the animation which is visible below:

Conclusion

In the end, the experiment was a success! I also took this opportunity to improve my software, which will benefit everyone. If you have eclipse scans, don’t discard them! Soon, you’ll be able to process them too.

The big question now is: Could this be done during a total solar eclipse, such as next year’s in Spain? Well, I feel lucky that this one was only 25% partial. Managing ellipse detection and mount realignment between scans is already quite tricky. During a total eclipse, there wouldn’t even be a reference point!

Unless one has flawless alignment, a mount capable of returning to position perfectly, and a steady scanning speed, this would be a real challenge. Honestly, it’s beyond my current expertise—it would require a lot more work.

P.S: For french speaking readers in west of France (or simply if you are nearby at that date), we organize the Rencontres Solaires de Vendée on June 7, where we can discuss this topic!